A Dream of opera turned to reality

Singer-composer Niki Main participated in a multidisciplinary course to produce a brand-new 20-minute opera. “We ended up with a smooth-sailing and close-knit group whom I’ve trusted with my share of the work from beginning to end, without hesitation.”

Moving for my operatic dream

In the interview portion of my entrance examination to the Sibelius Academy I was asked, “what are your goals as a composer for which you feel the need to study here, on the other side of the world?”

“I want to work in opera, as both a composer and singer. I don’t yet have all the tools I need to make this a reality, and Sibelius Academy will be the best place to study these”, I replied.

The Finnish professor showed a look of surprise at my clear answer. I continued by expressing that alumni of Sibelius Academy’s composing department demonstrate through their musical output an exceptional grasp and knowledge of the repertoire which I wanted to learn. In doing so, even the most avant garde textures still have an underlying lyricism and dramatic precision which make them approachable to musicians in a variety of backgrounds, including bel canto-trained opera singers with whom I plan to work extensively.

Beginnings of the Opera as a Multidisciplinary Collaboration course

In 2022, the second of my 5.5-year degree, UniArts launched a new course: Opera as a Multidisciplinary Collaboration. The course taught an intro to the creative process surrounding opera and set up composers and singers from Sibelius Academy with directors and writers/dramaturgs from the Theatre Academy to collaborate on new 20-minute mini operas. I didn’t participate in this first run, but the module was offered again two years later, in 2024-25, in which I participated as both a composer and singer.

Before we formed working groups for the course, we had several lectures and class discussions on the strengths and difficulties surrounding opera. Recurring themes in these discussions included:

- Differences between an opera libretto and script for a play. What sort of texts work when sung which wouldn’t work spoken and vice-versa.

- Differences in directing opera (as opposed to spoken theatre), where the rhythm, timing, and inflection are often predetermined by the musical score.

- Differences in compositional process and priorities when writing music for stage vs concert hall.

- Needs and working processes of singers and musicians as opposed to actors.

- Aesthetics and stylistic movements in each other’s (non-opera) mediums and the significances those have on creating and artistic identity now.

- The differences between opera as a genre and opera as a medium, i.e. what aspects are stylistic choices rooted in the tradition that is western classical opera, as opposed to structural elements of the art form at its root.

- The complex power dynamics between director, conductor, composer, and librettist who may all have conflicting wishes for creative direction and use of resources such as budget or rehearsal time.

With these themes in mind, it became clear to me that the most important thing in a multidisciplinary collaboration is having compatible collaborators. We had a chance to get to know all the other students in the course and discuss artistic interests and working practices before requesting our groupings. By the time we wrote to the professors our grouping requests, I was not only clear on my own preferences regarding aesthetics and processes but also had an idea of who in our course held these in common with me. We ended up with a smooth-sailing and close-knit group who I’ve trusted with my share of our work from beginning to end, without hesitation.

Working as a group towards a unified vision

We began with two librettist-dramaturgs, two directors, a tenor singer, and me (composer & countertenor singer). At the beginning our librettists planned to create a comedic piece on the theme of athletics. I’ve never particularly been a fan of any sports, so this was completely unrelatable for me. However, the writers’ reasoning resonated with me where the topic didn’t. They were intrigued by the similarities between performance as an athlete and performance as an opera singer: spectatorship, the reliance on a team or crew, and the pressure to keep oneself in top physical condition to perform at a superhuman level. We had a few meetings to brainstorm, experiment, and discuss wishes for the script and musical piece.

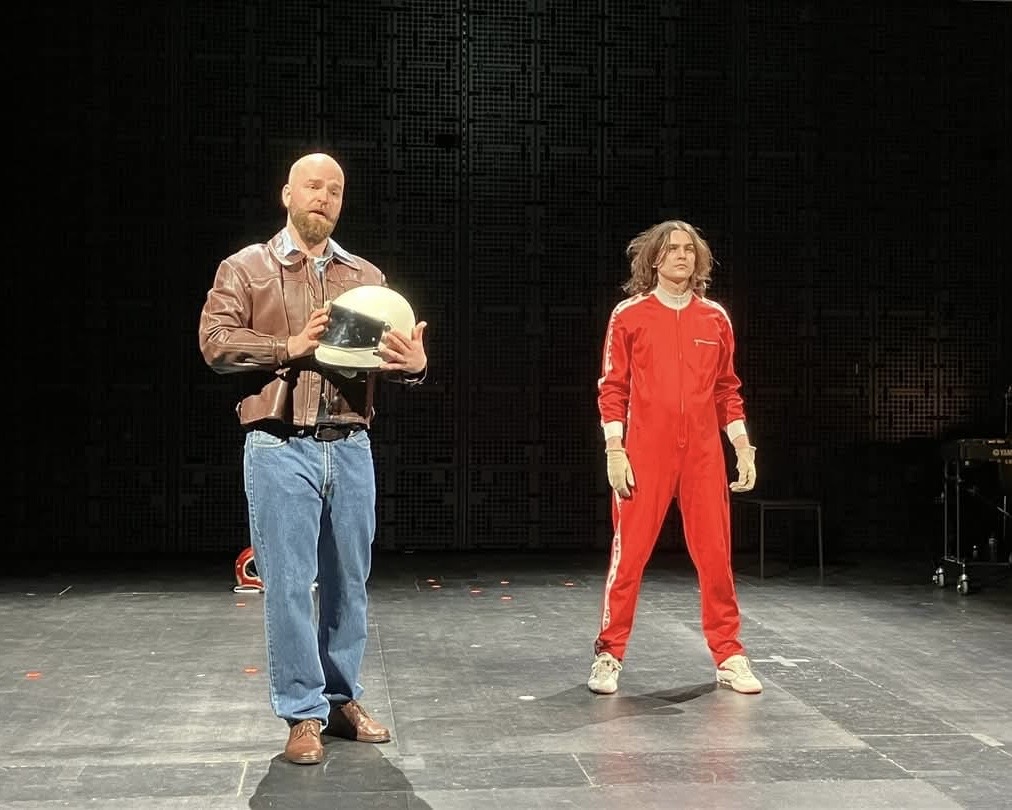

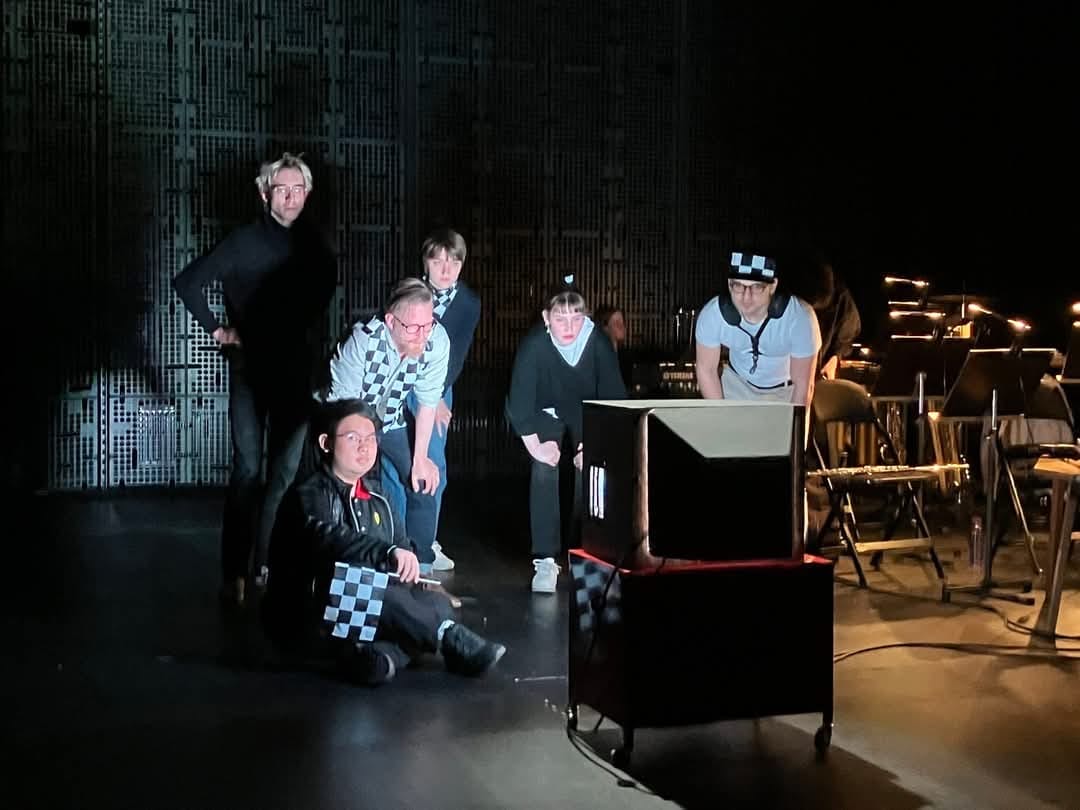

We were all excited to see what the writers would come up with and they were efficient in delivering an eight-page libretto. To our surprise, it wasn’t a comedy at all but a heart-wrenching tragedy on the topic of F1 driver Ayrton Senna’s death at the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix. The text was perfect. It accommodated an aria for each character and its vivid imagery, vocabulary, and story all lent themselves naturally to those high-emotion musical structures which opera has to offer. The six of us met several times reading carefully through the libretto as a group and discussing as many aspects about it as we could fathom. I began to compose.

Time was tight: I had less than four months to write twenty minutes of music for two singers and 8-piece ensemble on top of my usual school curriculum and other projects. I started with the large tenor aria at the end of the show. The emotional climax of the work, this dictated where everything would culminate—but I chose to start here solely out of practicality: I knew it would be the most vocally demanding section of the piece for the other singer, so I wanted to provide him with this material to begin learning as soon as possible. We continued to work in this way. As soon as I finished writing a new section of the music, it would be available for the singer and directors. This contrasts with my (and many composers’) usual practice of not showing the music until the score is completely done, but in a time-crunch putting aside my shame and trusting the collaborating team to view even unedited material without judgement was essential. The directors and tenor singer gave feedback about bits they especially liked and changes they wished for which helped me meet their needs with more care.

Opera is an expensive art form. All the usual production costs of theatre apply such as venue, rehearsal space, set, costumes, hair and makeup, and lighting, with the additional costs of hiring an orchestra, coaching and rehearsing singers, and—in the case of a new work—a commissioning fee for the composer. Especially with recent arts funding cuts, it’s a medium which is in danger and running a course for cultivating the creation of brand-new opera on virtually no budget proved challenging. Our creative team had to cut corners where possible and in doing so learned first-hand the importance of each step in the process.

But opera is a medium brimming with unimaginable potential. Our working group gradually expanded, adding a sound designer, a costume and set designer, and later a conductor and eight-member orchestra. With so many different artists brought together, each at the top of their game, the options felt limitless. Yet, despite this abundance of possibilities, since we had analyzed the libretto so thoroughly and were clear on the dramatic through-line, it never felt overwhelming. We made larger creative decisions together, such as some lines of text which we wanted to emphasize and whether passages would be delivered sung or spoken. Individuals or subsets of the group handled smaller decisions, and those would become known to the full group only later when relevant. Everyone had their part to do, and a healthy balance between being aware of the others’ parts versus having one’s own space to focus was key.

Coming to fruition

I worked several late nights composing, coordinating players and rehearsal schedules, and memorizing lines. It was demanding, but by the time we began full run-throughs during the week before the premiere, I knew our efforts would pay off.

During the last scene of our show, I exit stage right just a few minutes before the final blackout and house lights rise. I spent these couple minutes during the dress rehearsal watching the physically sparse yet emotionally charged stage action from the wings and feeling fulfilled. The work of nearly twenty artists put together over half a year to make our 25-minute opera had been a success. Now that the performances and afterparties are over, we’re excited to expand both this piece and, more broadly, our work in this medium. The dream I brought to my interview four years ago has not only begun to take shape—it’s come to fruition, and I can’t wait for it to continue to grow in the years to come.

Text: Niki Main

Photos: Eija Kankaanranta

Life of an art student

In this blog, Uniarts Helsinki students share their experiences as art students from different academies and perspectives, in their own words. If you want to learn even more regarding studying and student life in Uniarts and Helsinki, you can ask directly from our student ambassadors.

Latest posts

Follow blog