Interview with Spanish choreographer Cuqui Jerez

Last year Spanish choreographer Cuqui Jerez was one of the ANTI Live art Prize nominees. This year we had the pleasure to have her as a visiting teacher in the programmes of choreography and dance performance. During this interview we talked about Cuqui’s visit in Theatre Academy, and her work.

First I would like to ask you what have you been working on with the MA students this week in Theatre Academy?

C: A few years ago I did a project called Dream Project. I made 16 pieces over two-year time period as part of that project. I decided to do very short processes to explore working being very connected with the present, not projecting, not planning, not thinking of a production. I wanted to try to work a bit like a visual artists do, which is more day to day basis. Or with a very short process. I love long processes, but at some point I needed some kind of change of methodology.

So every month I was doing something different. I gave myself a task for each month, and at the end of the month I would close it somehow. I didn’t manage to do 24 pieces during these two years, because I had also other things to do, but I did sixteen, which was crazy.

S: Yes, it’s amazing!

C: And in fact, when I say pieces, it’s not how we conceive pieces, it’s more like articles. If we think about writing, it would be like an article. Some of them were performances, some were videos, texts, exercises, some were failures, some of them didn’t arrive anywhere…

So, one of those practices was called the gifts. It was a monthly practice but afterwards I transmitted this practice into a form of a workshop. And this is the workshop that the MA students got to experience this week. The workshop gives students tools, strategies and reflections to later use or adapt to their own artistic process.

The practice consists of methodology, that emerged when I got a commission from a festival in Switzerland. They proposed me to do a performance without the artist being present at the festival itself. It was a challenging process to do a performance without being there.

I realized that making a gift is something very similar to making a performance.

At that point I was at the Mexico City and I thought, what can I do that doesn’t make me to be in a studio, or at home, since I wanted to explore the city. So, I created these rules: I would give myself a daily mission, and in this daily mission I would produce a gift to unknown spectator, who will be in Switzerland at the time of the festival. This mission would produce an object and a letter. I did this every day during a one month, so I ended up with 30 missions, 30 letters and 30 gifts.

I did this because I realized that making a gift is something very similar to making a performance. We as choreographers, as performers, spend our lives doing things for somebody we don’t know, which is the spectator. It is a great analogy to artistic process or artistic research. During the workshop the students had their missions and every day they came up with the letter and a gift, and then we would share this every day. After sharing all the material we analyzed what was going on in terms of methodologies, dramaturgy, desire, subjectivity, devises, you know, all the things that I work normally with artistic process but now with a very concrete task.

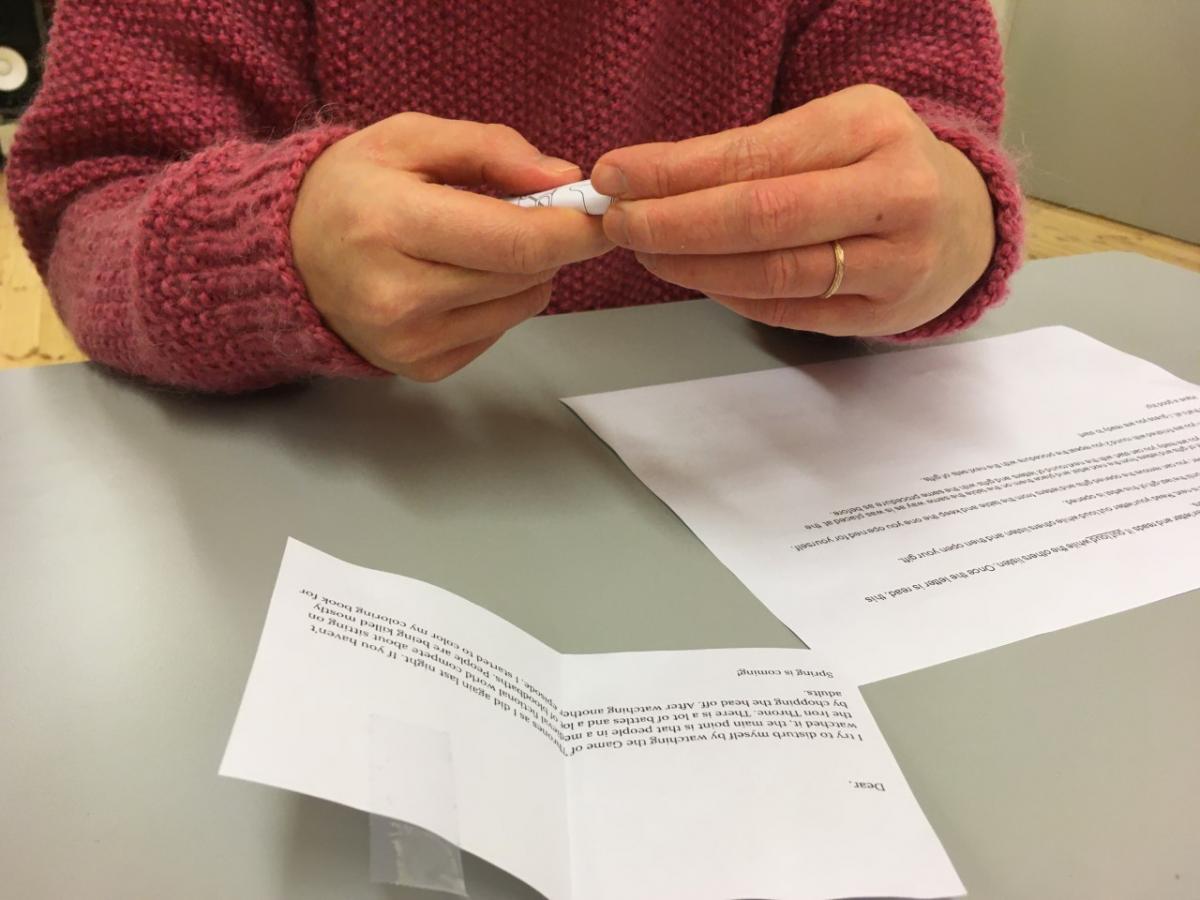

In the following week after the workshop the students prepared their gifts for the performance on Wednesday. I also took part to this performance event with 14 other spectators from the university. We got to open three presents with letters and share this with small groups that were seated at the same table.

For the most part we did not know who had made the gifts, and there was interesting intimacy to it. There was a sense of great generosity in the act of sharing of something intimate and personal with us. The act of opening the gifts together, and being witnessed by others, felt soothing in the context of performance where you mostly (even still in the time of so multifaceted performance sceen) face the performance by yourself. In a way we become the performers of this piece as well.

Cuqui says that the process of making a gift is a good analogy for making performances. I agree. I felt that receiving a gift is a good analogy for seeing/experiencing one as well. Opening gifts together resonates with birthday parties and Christmas, and there is this shared merriness in the air because of it. I wonder, how often is this atmosphere present in performances and what are the factors that make us be resentful, judgmental or just not fully arriving there with our attention?

You mention desire as one of things that you analyze with the students. What have you discovered about desire in relation to these workshops?

For me desire is something absolutely crucial in artistic practice – desire and pleasure. So, we’re talking a lot about how important it is that the motor of your practice is desire, something that you really need to explore, really need to learn – that there is a kind of urgency. We even talked about artistic practice as a kind of object of love. Me personally, I’m in this kind of in love state when I’m creating.

Of course, sometimes it’s not super easy to have this, especially if you are starting to create your own work, and you have an input from outside, which is the case here. Sometimes you are able to bring your desires when you are super free. So, we tried to find a way for the students to find their way into my methodology, but still find a space for their desire and their subjectivity. I didn’t put any conditions on what they wanted to do, what were their missions, what is the kind of writing… I make clear and concrete rules but within the rules all the space is yours.

Your work is often described as unconventional. Do you find it hard to be unconventional, and do you have some kind of tools for yourself to hold space for this kind of openness and creativity?

C: No, I don’t find it hard at all, it is the other way around. I find it super liberating, that’s why I do it actually. I think what is interesting when you work in contemporary art, is to be aware of the history, what others did and how the conventions are build. I don’t want to break conventions because I want to break conventions, but because I reflect around them. Sometimes I realize they are marvelous conventions and sometimes that some others don’t interest me.

Like for example theatre, it’s in itself a big convention. Already the machine of the theatre, theatre as devise. But I think it is one of the most beautiful conventions ever, to have the possibility to be a spectator, to be there in the dark watching the things. This is precious to me. But this doesn’t mean that within this convention you can’t break modes of operating. And this I what I do. I displace the gaze of spectator, offer other kinds of looking. In my early works I was very busy questioning what is performance itself. It’s not breaking conventions because I want to, but because I’m fascinated by them.

There are different levels of what language is and sometimes it’s really close to perception.

On your website you talk about time as something that enables transformation in space and space-time relation as something that activates language (or can help escape from it). You also say that your work has shifted from semiotic field to understanding the performative act as something that moves away from meanings and references.

(my question after this was so weirdly formed that I will just give you Ququi’s brilliant answer instead)

C: Language enables a performance itself, because otherwise we won’t be able to be, to exist, to survive. With the performance it’s the same. I’ve been always busy understanding language, but this also implies understanding the limits of it. There are different levels of what language is and sometimes it’s really close to perception. It’s really close to a space where we can’t put words to it but still perceive. And in this sense, in relation to temporality, time can be experienced in different ways, and not only in a way we maybe think is more related to linear time or the dramaturgies more constructed. A performance that brings you there and there and there and there…

At some point I started to explore different temporality, which is more like a landscape. There language doesn’t operate the same way. I as a spectator have the responsibility and the freedom to navigate through it. And maybe that’s the difference that you are mentioning, in terms of do we consider performance as a relation of signs or is it a space where I don’t necessarily need to organize or order, but I have the space to perceive it.

As a last question I asked, curious for advice myself as a maker in the beginnings of my track: “Can you recall an important lesson or experience that had a strong impact on your artistic thinking?”

Cuqui tells me that being a spectator, having interesting moments for oneself in the audience, have had a great influence for her work. She also mentions the importance of the work that she has done for other choreographers as a performer. When she was already at the track of making, she collaborated a lot with her sister María Jerez. This was an important phase, where she was not a performer for others with a bit less responsibility, neither the only one with it. The work and life with her sister since the day they were born seems to carry a special value for her. Hearing this makes me think of the importance of interconnectedness in art making, and to wonder, what might be the perfect mix of solitude and community for my own artistic processes.

What remained with me from this encounter is the emphasis on love, desire and playfulness that radiates from her and her thoughts – and got to experience in the demo of the students work. I find it inspiring to think about performance as a gift to the audience or the world. I also think there is a great value on being able to give a gift. There is a great potentiality for empowerment and solidarity wrapped in it.

All the truths we cannot see – a Chernobyl story

All the Truths We Cannot See: A Chernobyl Story is an opera by Uljas Pulkkis and Glenda D. Goss. It is produced as a collaboration between Uniarts Helsinki’s Sibelius Academy and the USC Thornton School of Music. Students from these institutions join forces in an opera production, which will premiere in Helsinki on 15 March 2022. The American premiere will take place in Los Angeles on 21 April 2022.

All the Truths We Cannot See: A Chernobyl Story explores the explosion that happened at a power plant in Chernobyl, Soviet Union in 1986, as well as its reasons and consequences.

This blog reveals the background stories and people behind this project and also represents some expert articles discussing the relation between opera and the environment.

Read more about the All the Truths We Cannot See: A Chernobyl Story opera

Latest posts

-

Jasper Leppänen: One of the biggest tragedies of human history

-

Tuomas Miettola: Nature against humans and their irresponsibility

Follow blog

How did Cuqui Jerez’s role as a visiting teacher at the Theatre Academy build on her previous connection to the ANTI Live Art Prize, and what insights did she share during the interview?

Visit us IT Telkom

IT Telkom

28.04.2025 10:24