Misbehaving with Classical Ballet – Why Study Theory at Uniarts?

Henna Raatikainen is the first student in the new theoretical research option of the Choreography MA Programme at Uniarts Helsinki. She is especially interested in formulating playful suggestions for classical ballet to interact with more experimental choreographic practices.

A year ago, in January, I froze. I was meant to be writing a newspaper article on ballet, but instead I was scrolling on my phone. The algorithm had done its job: on social media, an announcement from the University of the Arts appeared. “New Study Option: Theoretical Research in Choreography (MA)”.

I had not been planning to study again. I held a Master’s Degree in Social Sciences, and after years in communications work, I had also become a freelance journalist and dance critic. I liked that life – I liked writing about dance, as impossibly hard as it is. I was fine.

In 2023, I published a collection of essays on ballet. It circled around a contradiction I have never been able to resolve: I love ballet, and I hate it. Trained at the Finnish National Opera Ballet School, ballet lives in my body and in my thinking, even as its rigid structures and exclusions have become increasingly impossible to ignore.

But although I hadn’t articulated it, I had become restless. I was longing for slowness and being intentionally lost: for learning that is not turned into immediate output. Writing the essay collection sharpened this discomfort. Whenever I wanted to go deeper, the form pushed back. The publishing process, and even the book format itself, seemed to say: don’t go that far. Keep it readable. Keep it light. Don’t dwell.

The same thing kept happening in my other work. Writing for a newspaper is built on clarity and structure: who, what, where, how. While I enjoy writing such stories, what I kept asking outside the writing process was the why. Why does ballet – or any dance, for that matter – look the way it does? Why do certain art forms carry power and money, while others remain marginal? And especially: why do I, as a critic shaped by ballet, interpret and respond to performances the way I do?

That was why the Uniarts announcement struck me: “Students of the theoretical research option will deepen their analytical understanding of choreographic premises, potentialities, and various discourses while working alongside the artist-practitioner students,” it said. Analytical understanding! Choreographic premises!

Fast forward to the entrance examination. There they were on my screen, the professors and teachers evaluating me, and I heard something unrecognizably sentimental come out of my mouth. Who was this person rambling on about how encountering this programme felt ‘like a dream’? What a syrupy thing to say.

Yet it was true. That such a pilot programme exists – here, now, in Finland – feels highly improbable, radical even. In a time that demands productivity and constant visibility, it offers the possibility to take dance, choreography and bodily experience as seriously as they should be taken.

Inspiration and Horror

It has now been a year since that freezing: realizing that I should probably apply, then wrestling with an inner resistance, and then doing it anyway. Based on the first semester, the new study option has revealed itself as an inspiring blend of practice, theory, and critical writing.

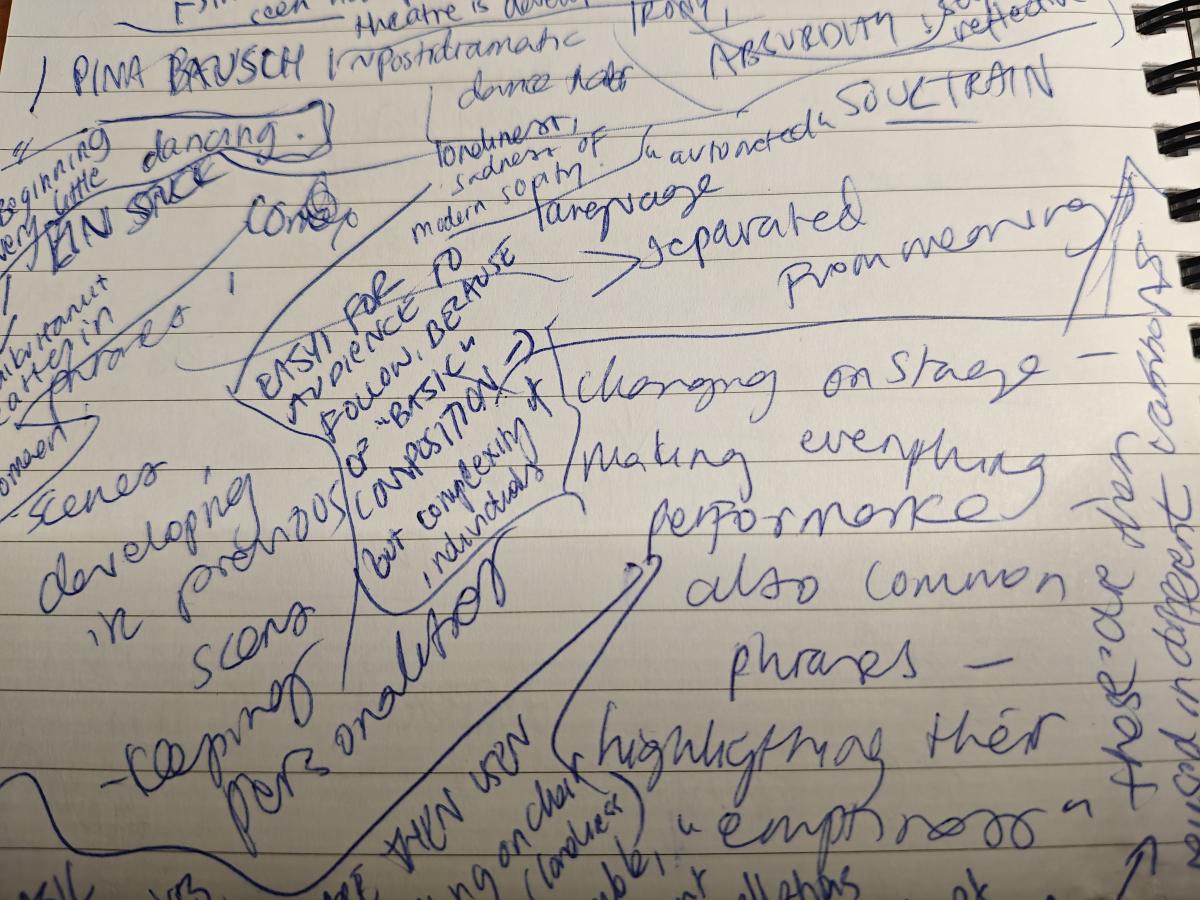

I applied to the theory programme with a research question about how classical ballet’s rigid formal constraints might interact with more fluid, experimental choreographic practices. During the first months of studies, however, contemporary choreography and performance theory threw me in every direction at once. I distanced myself from questions concerning ballet.

The distance proved productive. It allowed me to see ballet not only as something I had lived inside or as an object of sociological study, but as something to be examined and questioned from the viewpoint of choreographic frameworks.

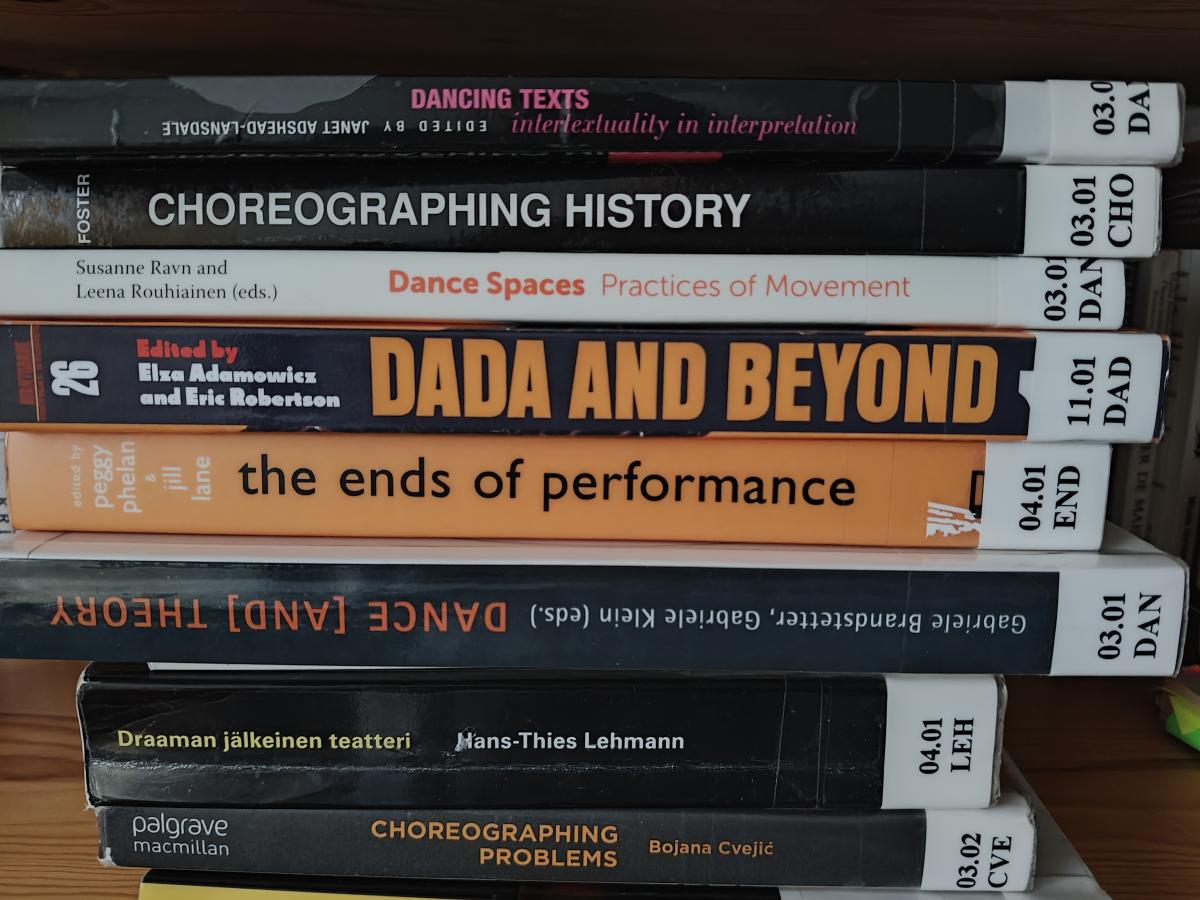

Professor Kirsi Monni customized a thoughtful reading list for me in order to both introduce the canon of dance studies and theory – Susan Leigh Foster, André Lepecki, Jens Giersdorf, Janet Lansdale and many others – and to allow me to delve more deeply into my own specific interests. I have already acquired a range of new vocabulary and frameworks to guide me forward. What I hadn’t anticipated was in how many ways sociology and choreography overlap. It’s not a surprise: both are concerned with organizing human relations, just at different scales.

Especially valuable has been the possibility to observe fellow students’ practices and creative processes. For this I am greatly thankful to the MA Choreography cohort, with students from different cultural backgrounds and dance practices ranging from street dance to acting and contemporary dance.

Blending choreographic practice and theory is, in my opinion, the very strength of this new programme, which does not treat them as separate but entwined. Discovering how practice and theory interact, illustrates, in a broader sense, why this programme matters, especially in a cultural landscape like the Finnish one, where bodily experience is often undermined by “thought” or “rationality”.

In her introduction to a collection of essays called Choreographing History (1995), scholar and choreographer Susan Leigh Foster writes, “A serious consideration of body can expose and contest such dichotomies as theory vs. practice or thought vs. action, distinctions that form part of the epistemic foundations of canonical scholarship. […] Are not reading, speaking and writing varieties of bodily action? […] Critical focus on the body forces new conceptualizations of these fundamental relations and of the arguments addressing individual and collective action that depend on them.”

And then for the horror. While I value this approach, attending workshops and participating in practices led by choreographers and artistic researchers have thrown me far outside my comfort zone. Coming from no art school background apart from the highly formal ballet training, participating in some of the Uniarts workshops has – in all honesty – been absolutely terrifying.

Bur the horror has been worth it. Experiencing different choreographic practices in group settings has heightened my respect for choreographers, artistic researchers and dance artists alike – and for group work, especially. It has also led to changes in my own writer’s practice.

Surprising Myself

At the end of last semester, we presented our first demo works. What was not surprising was that after a few months apart, I found myself face to face with ballet once again.

What did surprise me – and probably Professor Monni and our other supervisor, Lecturer-Researcher Jana Unmüssig – was that I did not create a demo by deep-diving into theory. Instead, I realized that I had begun to think choreographic thoughts, so to say. I had specifically begun to understand time, art form-specific temporality and practice-specific rhythms as playful materials.

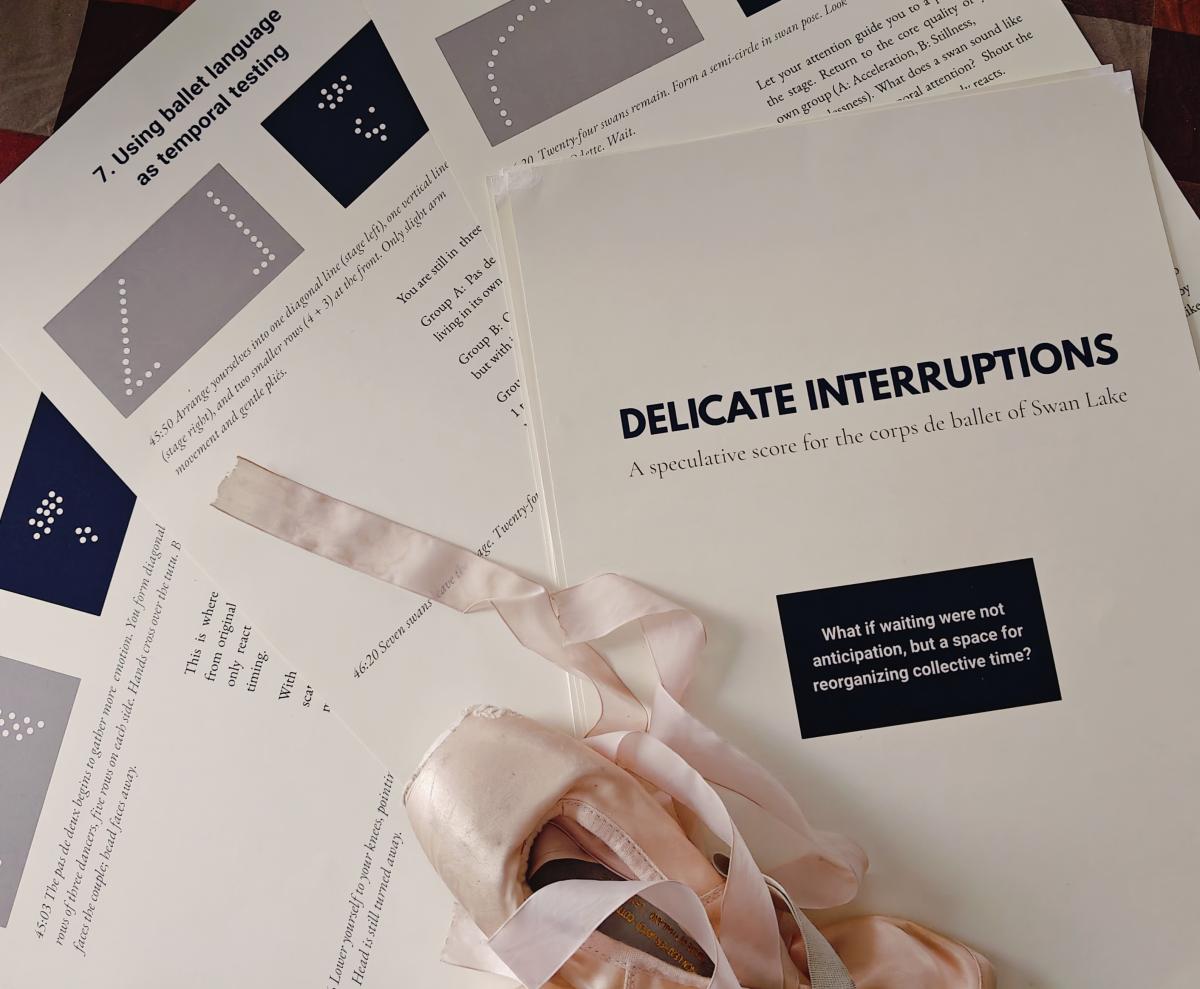

For my project Delicate Interruptions, I created a speculative choreographic score and an essay. I wanted a clash of thinking: using choreographer and Judson Dance Theater founder Deborah Hay’s attention-based method to intervene in the iconic ballet Swan Lake.

I centred the corps de ballet (the ballet ‘chorus’) in one specific scene and asked: Could shifting attention and perception change the focus and temporality of the group – and, as a result, the whole work?

In the famous scene, the corps is traditionally constrained to wait, still and synchronized, while the protagonists, Swan Queen Odette and Prince Siegfried, drive the narrative. I created an alternative that allows the corps dancers to generate their own impulses, subtly destabilizing hierarchical structures and revealing how new temporal arrangements might offer possibilities for collective agency within a historically fixed form.

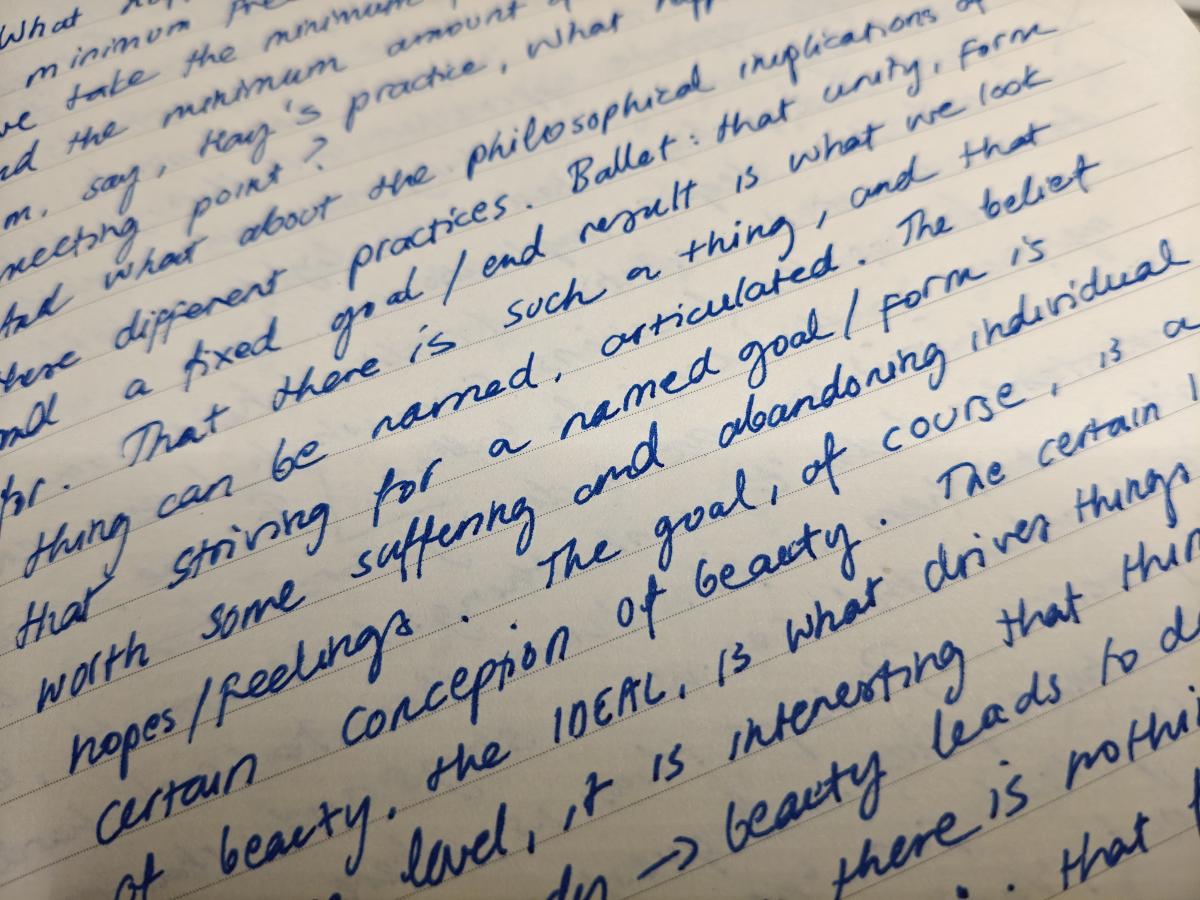

In the essay accompanying the score, I positioned score-writing as both critique and inquiry. While this aligned with the questions with which I applied to Uniarts, the project took me towards a creative, hands-on attitude toward using theory and melting it into artistic practice. As I wrote, I became obsessively interested in the intersections of choreography, spectatorship and writing. The project left me wondering whether choreographic scores could work as an experimental form of art criticism.

Spring with Dada

Building on my research into how classical ballet’s formal constraints interact with experimental practices, I have found it precious to encounter fellow choreography students for whom ballet is a mystery – even a “what the fuck?” While I am not on a mission to dismantle or deconstruct ballet entirely, I am eager to turn more deliberately to questions of active or disobedient spectatorship – both as a subject in itself and as a component of art criticism.

The theory studies are offering me tools to explore new ways of looking at classical ballet and, as a practice, to suggest speculative ways for the art form to reflect on itself. I currently divide these possibilities of artistic research into four underthemes, and present them as modes of speculation and playful thinking rather than as ends in themselves. They are: 1) Collective attention and perception (as in my demo project), 2) Active or disobedient spectatorship, 3) New dramaturgies and 4) Dismantling (ballet) language as a form of autocritique.

Inspired by conversations with choreographer and Uniarts alumna Giorgia Lolli, with whom I share a history and fascination with ballet, I’m busy pondering on number 4 this spring. Lolli’s new work BODY SWEATS, to be premiered next summer, tests ballet language as a corporeal and cultural archive to be deformed and rewritten. The work’s title cites the collection of poems by Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, a Dada-feminist artist, who writes of a body that rejects form. What, then, can dissecting, dismembering or dismantling grammar and syntax mean in the context of ballet language? How may ballet language be re-semanticized?

Just like Deborah Hay’s approach, Dada, Lolli’s work, and Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven’s poetry, serve here as tools for intervention: reminders to conceptualize and “test” ballet from outside ballet. Ballet is not only a bodily practice, but a system of seeing, training both dancers and audiences to recognize a “right” and “wrong” way to move and look. Can spectatorship, then, also be re-choreographed to generate alternative values within ballet?

On a personal level, holding power as a dance critic requires asking how my own gaze and values have been shaped. This is why I play with the idea of challenging and reconfiguring my own critic’s gaze. I think about my editors at the Big Newspaper receiving a critique of a classical ballet written in Dadaist spirit. Something like: Giselle! New? Old? Crash! First act mashed, flipped, women laugh. Second act curtsies, trips, whispers and weeps. Original? Maybe? Times slip, tumble, crooked things finger tradition. Clap. Audience corpses, corps leaves. Who counts? Who bleeds?

Written by Henna Raatikainen

Choreoblog

A place for discussion and sharing, the blog for Master’s Degree Programme in Choreography brings together students, staff, and visitors to write and read about choreography, studying, ongoing projects, (dance) art, and related topics.

Latest posts

Follow blog