Swimming with the Trouble

Orla Mc Hardy wonders if contaminants and cyanobacteria are agents and provocateurs that challenge perceptions of everyday encounters.

Orla Mc Hardy

When flying out of Helsinki international airport last week, I was struck by the last minute souvenirs on sale in departures. There was the old school variety; keyrings and fridge magnets with images of pine trees, wooden cabins, Finnish flags and reindeers, as well as every sort of variation of Moomin-as-product. Another trend in souvenirs caught my eye – best described as aspirational. These souvenirs, bought into a human desire to connect with nature, and in the process have an enriching/rejuvenating/relaxing experience. The nature that we were being tuned into were the images of pristine forests, rivers, lakes and the coastline of Finland, which we could access from afar by purchasing a foot massage rock, beard balm, scent diffuser, hand woven scarf, a reindeer hide.

A particular product caught my eye, a collection of towels designed and woven in Finland with the eye-catching slogan ‘Clean Baltic Sea’. How to read this? As a statement of fact, or as a call to action? I had just learned about the algal bloom that occurs in the Baltic Sea around the Helsinki coastline. The situation is so bad that the Finnish Environment Institute has a constantly updating website to show the levels of the “blue-green algae situation” which can change quickly especially during the Summer months as the water warms up. The situation is so dire, they lead with the alarming message: “Summer water is enticing to swim, but the beach water seems to be greening. Do you dare to go swimming?” [1]

The “blue-green algae situation” is caused by cyanobacteria; microscopic single celled organisms which use sunlight to make their own food. They occur naturally in fresh, brackish and salty bodies of water. The small and shallow Baltic Sea is an ecosystem particularly sensitive to pollution, where eutrophication is one of its greatest pollutants. Eutrophication happens when excess nutrients, in particular nitrogen and phosphorus, end up in the sea as a result of run offs from agriculture and industrial waste processes. This causes an overabundance of cyanobacteria and plants. On decomposition they produce large amounts of carbon dioxide which lowers the pH of the sea water in a process known as ocean acidification (OA). [2] This is hugely detrimental to marine organisms and ecosystems as the reduced calcium carbonate (CaCO3) saturation state impairs calcification rates of plants, fish, bivalve mollusks and animals that use carbonate to build their shells and skeletons.

Around the world, algal blooms caused by cyanobacteria are closely monitored as an indicator of water quality and as a visual marker of how bodies of water are adversely affected by pollutants and climate change. Due to their toxicity to water, plants, animals and humans, algal blooms are controlled when possible. [3]

In her 2019 project, Holding the Herbarium [4] which forms part of an artistic-research project, Speculative Subjectivities, artist researcher Helen Hunter documents her encounter with samples of cyanobacteria algae preserved on sheets of paper at the Natural History Museum of London. The material outcome of these “creative methods of noticing,” [5] a method which Hunter credits to Lowenhaupt Tsing,[6] is a poetic text-image piece, taking in the multiple spaces, temporalities and modes of sensing present in the archive – the building that holds it, its occupants, their possessions, life on the street outside, its heating system, an imagined consciousness of the cyanobacteria, her own patterns of breath. As Hunter writes, “In here everything becomes data.” [7] Hunter identifies this process as an ‘intra-action’, a concept introduced by Karen Barad. It describes the “mutual constitution of entangled agency, that is the mutual constitution of our ability to act. When two entities intra-act, they do so in co-constitutive ways. This means that agency is not a pre-existing given. The ability to act emerges from within the relationship, not outside of it. And this ability constantly changes and adapts according to processes it is involved in.” [8] With the project, Hunter reminds us that cyanobacteria has “the potential to destabilise human exceptionalism and the privileging of human history by pointing towards the precarity of a situation, in which algae has the ability to create and take life.”

Teal sutures

pinch in

flayed derma

fringes outwards

sand in your filaments

holds on

at the edges

wavelets

double back

retreating classifications

calling out for water. [9]

In Worlds of Gray and Green, Sebastián Ureta and Patricio Flores, use an experimental ethnographic lens to analyse the waste products that spill from Chile’s El Teniente, the world’s largest underground mine currently made up of 3,000 km of tunnels. In doing so, they challenge us to rethink extraction as ecological practice. Tailings are a byproduct of mining. At the copper mine of El Teniente, each copper ton creates approximately 99 tons of tailings. This waste stream of residues must be removed quickly from the plant. Tentiente tailings, mixed with huge quantities of water travel across a purposely build concrete canal for 85 kilometres until they reach Carén Dam, where they spill out so that as far as the eye can see is what looks like grey lifeless water. The dams that contain tailings “usually become enormous, extending for hundreds of square kilometres and reaching depths of several hundred metres” making them “probably the largest man-made structures on Earth.” [10]

However, downstream from the Carén dam wall, their view contradicted the ecological destruction they had come to associate with tailing ponds. They came across a valley teeming with life. The water required to move the slow moving tailings, ended up in this valley after being treated to remove the toxins. This formed into a lagoon, bringing water for plant life, animals, birds as well as supporting the growth of agricultural crops. In Carén, they found “tailings causing both disruption andemergence of life, usually in the same movements.” [11] Following on from Donna Haraway, they chose to stay “with the trouble of tailings”, which “necessarily implies properly seeing them, assigning them analytical and ethnopolitical space, and recognizing in them a certain dignity, even a right to existence.” [12]

Back to towels in airports, to towels next to unswimmable beaches, back to the production of unnecessary things. My initial scepticism is complicated, when on further research, I learn that the ‘Clean Baltic Sea’ slogan is indeed a call to action – albeit action through consumption – as it is produced by the Finnish linen and wool weaving mill, Lapuan Kankurit, who since 2017 have been cooperating with the John Nurminen Foundation, with the aim of supporting their “Clean Baltic Sea projects advance the protection of the joint, unique marine environment,” where “cooperation is a natural part of the activities of a responsible, design weaving mill using natural materials” [13] How to understand and live through these contradictions? Cyanobacteria draws, or more accurately, submerges us in glowing greens and blues, our attention to the complications of cross-species intra-relationships and to the implications of our everyday actions (or inaction) within a capitalist paradigm.

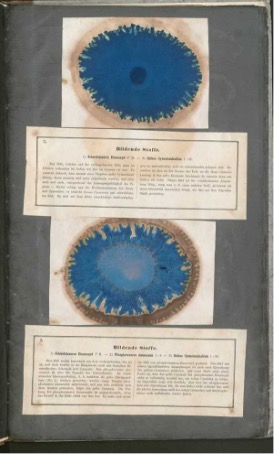

Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge was a German analytical chemist, a friend of Goethe, and best known for his discovery of caffeine. He was interested in the chemistry involved in aspects of everyday domestic life and in turn made sure to make his discoveries accessible to a wide audience, including housewives and children. In 1855, Runge self-published Der Bildungstrieb der Stoffe: veranschaulicht in selbstständig gewachsenen Bildern (The Drive to Formation of Elements: Made Visible in Independently Grown Images), a catalogue of images formed by dropping various of chemicals on blotting paper. He carefully scrutinised the patterns and colourings that formed until he learned through slow observation which combinations gave what effect and colour range. Runge believed his materials had agency. In an echo of Barad’s intra-action, he wrote “the chemical behaviour of an element depends on its chemical activity, and this activity is its peculiar expression of life when confronted by another element.” [14]

Runge’s slow attunement to chemicals and their agency is an entry into another way of seeing the environment in which we live, revealing our inseparable alliance with the plants, minerals and their chemistry. [15] Of image no. 20 of Der Bildungstrieb der Stoffe, he noted that a “great nature researcher says: nature reveals her secrets on the surface; I wish to add to this: and especially at the edges of this surface.” According to Esther Leslie, in her book, Synthetic Worlds- Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry, the edges “fascinated Runge because they were the representation of the last point of time in the history of the image’s formation. The edges are the end of the story, for all activity emerges from the centre where the drop falls, and the edge is the furthest away point in space and time.” [16] But what if the edges tell us the beginning of a different story? Maybe the edges are where we have to situate ourselves to begin imagining more agile narratives, stories of ever evolving knotty formations of co-existence? Tailing ponds, algal blooms on the shorelines of Baltic Sea, tea towel manufacturing plants, are examples of contradictory man-made geo-entities. Cyanobacteria act both as pollutants and can be harnessed to clean polluted waters. [17] Is it possible that they can propose a method of swimming with the trouble, where they become agents or provocateurs, challenging perceptions at the edges of everyday encounters?

Notes

- https://www.marinefinland.fi/en-US/The_Baltic_Sea_now/Algal_bloom_observations

- https://www.airclim.org/ocean-acidification-increases-agony-baltic-sea

- https://johnnurmisensaatio.fi/en/the-baltic-sea/eutrophication/

- Helen Hunter, https://maifeminism.com/holding-the-herbarium/

- Ibid.

- Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 2015.

- Helen Hunter, https://maifeminism.com/holding-the-herbarium/

- http://makecommoningwork.fed.wiki/view/intra-action

- Helen Hunter, https://maifeminism.com/holding-the-herbarium/

- Sebastián Ureta and Patricio Flores,Worlds of Gray and Green -Mineral Extraction as Ecological Practice, University of California Press, 2022, p. 10.

- Ibid., p.10.

- Ibid., p.10.

- https://www.lapuankankurit.fi/en/lapuan-kankurit-helping-baltic-sea

- Esther Leslie, Synthetic Worlds – Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry, The University of Chicago Press, p. 62.

- http://supercommunity.e-flux.com/texts/the-corruption-of-the-eye-on-photogenesis-and-self-growing-images/

- Shetty, K., Krishnakumar, G. Algal and cyanobacterial biomass as potential dye biodecolorizing material: a review. Biotechnol Lett 42, 2467–2488 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10529-020-03005-w

Artist Bio: Orla Mc Hardy is an artist and educator. Her work has been exhibited and screened internationally. Working through expanded animation, video, text, documentary, collage, sculptural installation and within a tradition of feminism(s), her current work examines where value is placed (and not placed) on the hidden time of care, love, labour and staying put.

Ecological Thinking

This is the course blog for K-JI-11-23A – Ecological Thinking. In 2023-24, we explore “Vertical Ecologies” by visual arts, film and performance. The course is co-organized by Giovanna Esposito Yussif and Samir Bhowmik. Previously, in 2022-23, we organized a year-long collaborative research studio with Aarhus University, DK, Research Pavilion 2023 and Helsinki Biennial 2023 on the themes of environmental data, sensing and contamination.

Header image credit: Abelardo Gil-Fournier and Jussi Parikka / Seed, Image, Ground (2020)- With permission from the authors.

Latest posts

-

Ecocidal Development and Atmospheric Warfare - Guest Lecture by David Muñoz Alcántara, 18.3.

-

"Schizophrenic relationship with nature" - Guest Lecture by Matti Aikio, 12.2.

Follow blog