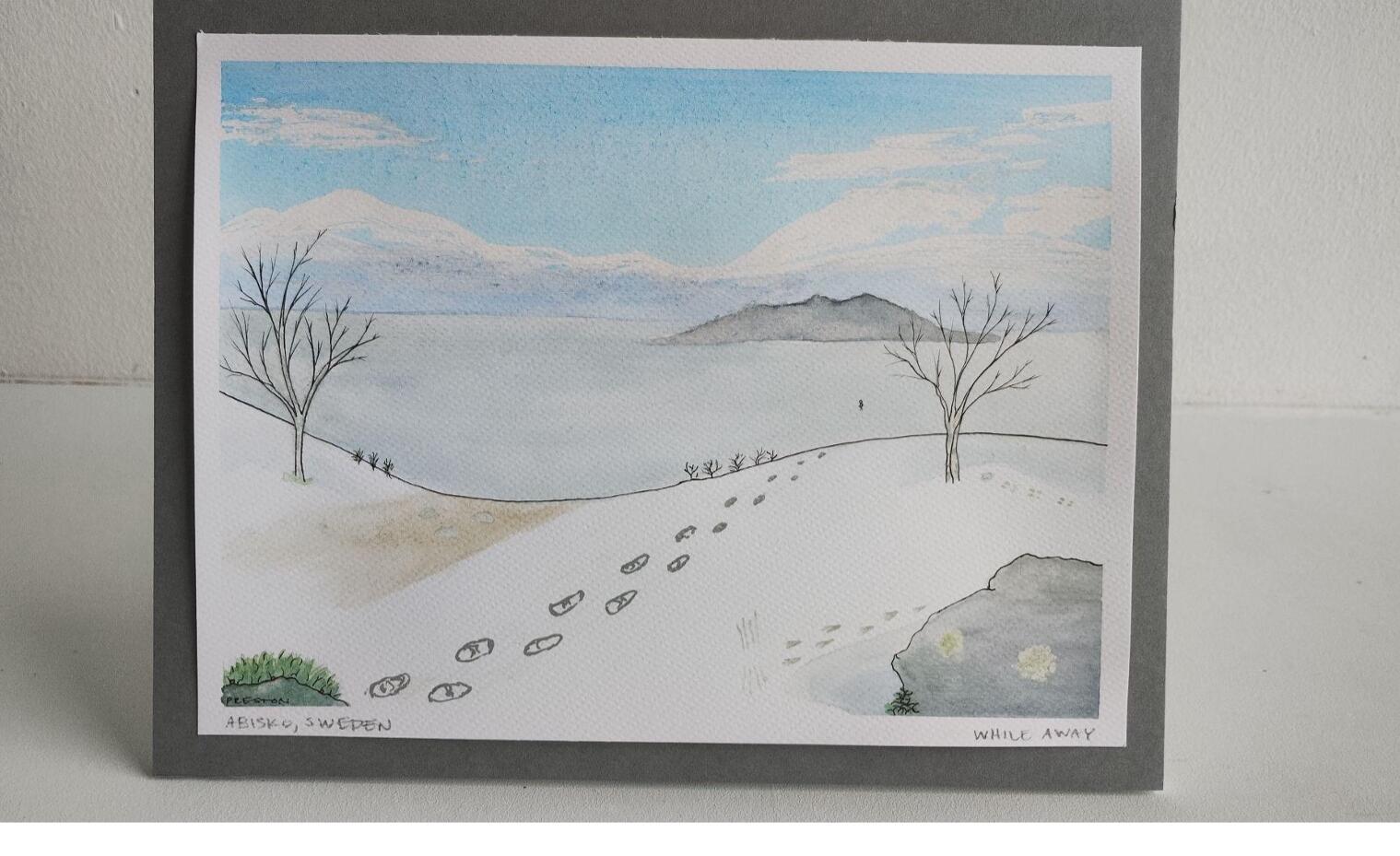

Traces? (Preston)

We live in a world of traces. Things leave traces. We must never try to make man believe that what is by definition constituted as a ‘trace’ has indeed a different kind of reality—that of ‘object’. (Foreman, 1976)

I pressed my nose to the window as the train approached Kiruna | Giron. Sápmi: age-old home to Sámi people, and more recently, Swedish state-owned iron mines. The mining landscape around Kiruna is more desolate than I imagined, an other-worldly sci-fi novel. As the train departed for Abisko I Abeskovvu1, the haunting minescape of Kiruna disappeared but left an indelible mark.

Nobody lives everywhere; everybody lives somewhere. Nothing is connected to everything; everything is connected to something. (Haraway, 2016)

Walking or snowshoeing is when I immerse in non-human life around me. Sometimes I think of the Windigo, from Native American teachings: a human whose selfishness has overpowered their self-control to the point that satisfaction is never possible. (Kimmerer, 2013)

I’ve snowshoed under wind turbines near Rena, Norway, and I find them fascinating. Until I learned their effect on reindeer (herding), I thought they were a great energy solution. I hadn’t understood the negativity: People, after all, destroy more land / nature / environment / life for roads to cabins they use twice a year, and they irritate me more than swooshing of blades.

While we may all ultimately be connected to one another, the specificity and proximity of connections matters—who we are bound up with and in what ways. (Van Dooren, 2014, as quoted in Haraway, 2016)

I was bound up with art students and professors from the Baltic area. We learned, discussed, evaluated, and reflected on extractivism humans increasingly inflict on our planet. It was an intense week at Abisko Scientific Research Station. Strong connections were made, and I have new ideas for how my artistic practice can interact with the outdoor spaces I love.

My travels from Trondheim ended on Norway’s busiest railway. Malmbanan (The iron line, Swedish side) and Ofotbanen (The Ofot line, Norwegian side) were built to carry Kiruna’s iron ore south to Luleå, Sweden and west to Narvik, Norway.² The railway is now also a tourist attraction winding its way through idyllic fjordland—home to Arctic wildlife.

Assemblages are open-ended gatherings. They allow us to ask about communal effects without assuming them. They show us potential histories in the making. (Tsing, 2015)

During a recent seminar at Trøndelag senter for samtidskunst3, Márjá Karlsen discussed her work as duojár (Sámi handcrafter), her activism, her studies—and her deep disappointment with the Norwegian government’s decision to support electrification of Melkøya near Hammerfest. Processing natural gas from the Snøhvit field in the Barents Sea would be electrified with power from windmill farms in reindeer herding Sámi land.4

Etter Alta5 har jo klima, miljø og naturvern blitt tre forskjellige ting.6 (Ossavy and Kolbenstvedt, 2021)

As I hear Sámi stories and learn about native culture and history, I wonder how we humans can learn to live with less, instead of presuming more is better— more electricity, more travel, more meetings, more merits.

1 áhpi = large lake, sea (Sámi) + skog (forest in Swedish). Lars Mæhlum, Store Norske Leksikon, https://snl.no/Abisko. Retrieved 29 May 2025

² Tor Wisting, Store Norske Leksikon, https://snl.no/Ofotbanen. Retrieved 29 May, 2025

3 Trøndelag Centre for Contemporary Art in Trondheim, Norway

4 Tina Andersen Vågenes, Naturvernforbundet https://naturvernforbundet.no/elektrifisering-av-melkoya/. Retrieved 18 June 2025

5Sámi people and environmentalists campaigned against hydroelectric development in Alta, Norway 1978-1982.

Mikkel Berg-Nordlie and Knut Are Tvedt. Store Norske Leksikon, https://snl.no/Alta-saken. Retrieved 11 June 2025.

6 Translation: After Alta, climate, environment, and nature conservation have become three different things.

From a text by Tale Næss and Trond Peter Stamsø Munch. En samtale om å sprenge ei bru

Text and images ©2025 Marie E. Preston

References

Foreman, Richard. 1976. How to Write a Play. Performing Arts Journal, Vol. 1, No. 2 (Autumn 1976): 84-92. https://doi.org/10.2307/3245042.

Haraway, Donna. 2016. Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene. e-flux, no. 75 (08/16), 03

Kimmerer, Robin W. 2020. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. Penguin Books, 306

Ossavy, Nina, and Marius Kolbenstvedt, eds. 2021. Naturtro—om å dekolonisere naturen. Iris Forlag / Concerned Artists Norway, 192

Tsing, Anna L. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton University Press, 22

Van Dooren, Thom. 2014. Flight Ways: Life and Loss at the Edge of Extinction. NewYork: Columbia University Press, 60.

Rare Earths

Rare Earths: Field Studies in the Extractive North is a KUNO Network funded course organized as the start of a multi-year research project between the Royal Institute of Art, Stockholm (KKH), Trondheim Academy of Fine Art (NTNU) and the University of the Arts Helsinki, Academy of Fine Arts.

Latest posts

Follow blog