Caring for children gifted for music: Who is responsible & is it really done?

Caring for children gifted for music is both a moral and political endeavor, and we all are responsible to care for and about them—but do we actually do it? If not, why? And if yes, can we do better?

Who is responsible?

When we think about children who are highly gifted—in music or in any other field—we tend to assume that parents and teachers are the people who play the most important role in caring for them. After all, it is all about nurturing and educating them, and who could do that better than such important figures in their lives? Although we should probably add grandparents to this list, we can also assume that, as gifted children go to (music) school or parks and socialize with other children, their similar-age peers represent another important group of people who should also care about them. And, in that line, their siblings, cousins and—why not?—their entire extended family should care about them too. Just because they are gifted in one field shouldn’t limit the field of people who care about them.

While caring “for” and caring “about” someone is slightly different—as the former implies a more active role than the latter—no one would doubt that children gifted for music deserve a caring ecosystem, just as any child would. This becomes even more important because these young (semi-)professional performers are often engaged in work meant for adults, and are thus a particularly vulnerable group of learners who are exposed to public scrutiny from an unusually early age. As we describe in our recent chapter on the systems of caring for the gifted (López-Íñiguez & Westerlund, 2023), they can be considered vulnerable because:

“…children gifted for music, when selected for advanced programs, may enter an “ableist” regime of technically defined and authoritatively prescribed musical competence goals instead of being cared for as genuine partners in human relationships and authors of their own lives.” (p. 119)

However, is caring for/about these gifted youths an issue that should only concern their family, teachers, and peers? Is this the entire ecosystem surrounding a child gifted for music? Or, should we expand our understanding of the potential size of this ecosystem? Perhaps we should first consider what an ecosystem is, and then return to the question.

Traditionally, the ecosystem of any child (included the gifted) is typically defined as an network of the interrelated structures that have an impact on that child. These structures were described by Bronfenbrenner in his “Bioecological Model of Human Development” (1996) and his “Ecological Systems Theory” (1977) as follows:

- the biopsychological organism (e.g., the child, simply put), and

- the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem (i.e., the societal structures around the child).

What these somewhat complicated words mean is that a child’s development is a combination of the child’s own personal traits and characteristics and their relationship with their environment. Basically, a child does not develop in a vacuum, but as part of their interaction with larger social structures. The child, as well as the constellation of their parents, teachers, peers, and extended family are not at all an ecosystem unto themselves—they are each only a smaller structure within it: the microsystem.

So, as I wrote in my previous post, we need to think about all of the others who also (positively and negatively) affect these children’s lives and development, and who, more often than not, should be caring for them in better ways: the audience, journalists and media, educational and cultural institutions, the music industry and its representatives, local governments (exosystems), and even entire nations and societies that follow widely shared cultural values, social norms, economic systems, welfare policies, and political and legal systems (macrosystems), as well as the changes over time that inevitably affect them all (chronosystems).

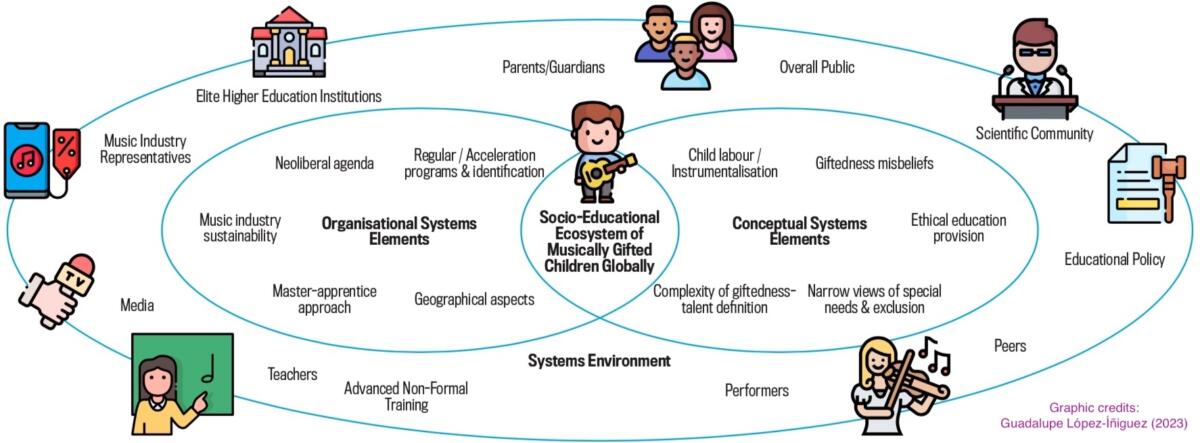

The Figure below illustrates some of these aspects, although organized in a slightly different system than that of Bronfenbrenner—to make things clearer (hopefully!). You can consider any of the stakeholders (i.e., people) represented in the figure and think about what kind of care they could provide to children gifted for music, and how important their role is in the children’s overall development and thriving. You could also think about some of the other elements in the figure, such as the programs for talent acceleration and how they relate to caring for these children.

The importance of these structures, along with their stakeholders, associated systems, and the complex relationships between them is not insignificant; if any of them breaks down and the child does not receive the support they need, it will hinder their ability to thrive and reach their full potential. For instance, you could look at the figure again and think critically about how the neoliberal academic agenda—which sees students as human capital (i.e., humans as profitable investments or products)—relates to caring … if at all. You can also morally twist your mind for a second (but, please, get back to normal quickly!) and think about whether it is possible not to care (this exercise will probably remind you about terrible examples in human history). As you can see by now, this system offers multiple positive and negative possibilities, and things quickly get rather complicated (as in Bronfenbrenner’s theory).

In my recent co-written chapter (López-Íñiguez & Westerlund, 2023), I refer to two types of structures:

- People who believe in (and might profit from) gifted children’s potential (a.k.a. pro-ableists, some of whom believe that people with certain abilities are superior than others) might lead to “lifelong trauma and abuse … parental oppression and exploitation … authoritarian behaviors of teachers … exposure to public scrutiny … child labor” (p. 117).

- People who are reluctant to admit that gifted children exist or need any additional support due to being part of a supposed elitist system (a.k.a. extreme anti-ableists), and who, despite all empirical evidence of their existence and vulnerable situation, tend to remove them from any educational policy discourse that would support them.

This crazy polarization is what makes these children even more vulnerable: that the entire ecosystem has for so long been concerned either about exclusively maximizing gifted children’s talent at any cost, or about neglecting their very existence, or even blaming them for sustaining a so-called elitist system. A rather tough place to be, and a rather heavy burden to carry, given that we are talking about minors. This frustrating rationale leads to another question:

Caring for children gifted for music is both a moral and political endeavor, and we all are responsible to care for and about them—but do we actually do it? If not, why? And if yes, can we do better?

Are children gifted for music sufficiently cared for?

I was curious to figure out what research says about whether people have genuinely cared for students gifted in music. In my recent literature review on the topic (López-Íñiguez & McPherson, 2023), we went through hundreds of publications on the matter that described different formal, non-formal, and informal learning situations, as well as different relationships between gifted and talented musicians with the stakeholders identified in the graphic above. What we found was rather striking: only 11 international publications described aspects of educating and nurturing these children in caring ways.

Our results suggested that “the existing research on caring approaches to musically gifted children’s learning and development are scarce” and that “current knowledge is based mostly on single one-off studies rather than systematic research, and on studies that examine a selection of aspects but not adopting a larger-scale theoretical framework” (p. 1). However, there were also positive aspects in the studies that related to care, for instance:

“…addressing inequalities in opportunity to access gifted programs; identifying socio-emotional needs of the gifted (and twice-exceptional) students; offering a nurturing environment; focusing on intrinsic motivation; developing coping strategies for overall wellbeing; and cultivating healthy attitudes toward competitions through a spirit of peer collaboration and humility.” (p. 1)

We can agree that these are all important themes; generally, it is good that gifted children are receiving positive support and that people look for ways to better care for them. However, as we concluded that the identified aspects are not enough—particularly given the advances in other general education areas—we suggested a few ideas on what else could be done and where future lines of research could proceed.

What could we do better?

We could endlessly discuss the various aspects that should be considered in order to better care for gifted children in music education settings. As this blog post is already rather lengthy, I will try to summarize the main points. First, we should really compare what we know from the excellent research and pedagogical interventions related to caring for the gifted in other areas such as general school subjects, as well as other highly demanding and specialized areas such as sports, and assess what could be adapted to the music field.

However, we should also develop a broader approach to musically gifted children’s education that “links this knowledge with broader national and international concerns such as human rights, ethics of care, and responsibility and laws that might protect highly gifted youth” (López-Íñiguez & McPherson, 2023, p. 13). For this, we need to undertake multidisciplinary studies to understand the complete ecosystem surrounding children gifted for music at the levels I mentioned above (Bronfenbrenner’s system), combining that knowledge with determining variables such as their motivation, learning mindset, and stage of development.

Expanding our conceptions of talent development within an environment that cares for the socio-emotional needs of gifted children is a priority for music education worldwide, and a powerful example of attending to inclusion and diversity in our music schools, music conservatoires, and music universities. I invite you to follow my research project (2022-2027) as I try to “care” that all these aspects are addressed, and we offer better futures and educational paths for gifted children. Stay tuned!

About this blogpost

This blog post has been written to mark the World Council for Gifted and Talented Children’s International Day of the Gifted, which is celebrated annually on August 10. The International Day of the Gifted is a global day of action to raise awareness around the world about gifted children and their learning and social/emotional needs. This post is part of the blog post series related to the author’s 5-years research project: “The Politics of Care in the Professional Education of Children Gifted for Music” (2022-2027), funded by the Research Council of Finland.

Read more about the World Council for Gifted and Talented Students

Read more about the “Caring for Musically Gifted Children” project

Cite as: “López-Íñiguez, G. (2023, August 9). Caring for children gifted for music: Wo is responsible and is it really done. Uniarts Helsinki’s Emerging Perspectives on Instrumental Pedagogy blog. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10470903”

Writer

Dr. Guadalupe López-Íñiguez, University Researcher, Academy Research Fellow, and Docent at Uniarts Helsinki.

References

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). “Toward an experimental ecology of human development”. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513–531.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1995). “Developmental ecology through space and time: A future perspective”. In P. Moen, G. H. Elder, Jr., & K. Lüscher (Eds.), Examining lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of human development (pp. 619–647). American Psychological Association.

- López-Íñiguez, G., & McPherson, G. E. (2023). “Caring approaches to young, gifted music learners’ education: A scoping PRISMA review”. Frontiers in Psychology, 14:1167292.

- López-Íñiguez, G., & Westerlund, H. (2023). The politics of care in the education of children gifted for music: A systems view. In K. S. Hendricks (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of care in music education (pp. 115–129). Oxford University Press.

Emerging Perspectives on Instrumental Pedagogy

This blog offers new approaches and viewpoints to instrumental pedagogy at all educational levels, from music schools to higher education. The particular focus of this blog is on student-centered pedagogies that prioritize the physical and psychological health of music students, support their socio-emotional development, and challenge overused power hierarchies in the music studio. The blog is written by Dr. Guadalupe López-Íñiguez, University Researcher, Academy Research Fellow, and Docent at Uniarts Helsinki.

Latest posts

-

Giftedness and talent in music: Nature, nurture, and/or luck?

-

Music education pathways for underage gifted learners’ talent development

-

The professionalization of gifted children in the performing industry: Who cares?

Follow blog