Exploring performative pedagogies in upper secondary arts education – learning as unlearning and risk-taking

Read a blog post by professor Kristian Nødtvedt Knudsen who is part of Nordic performing arts research team in SMIL project.

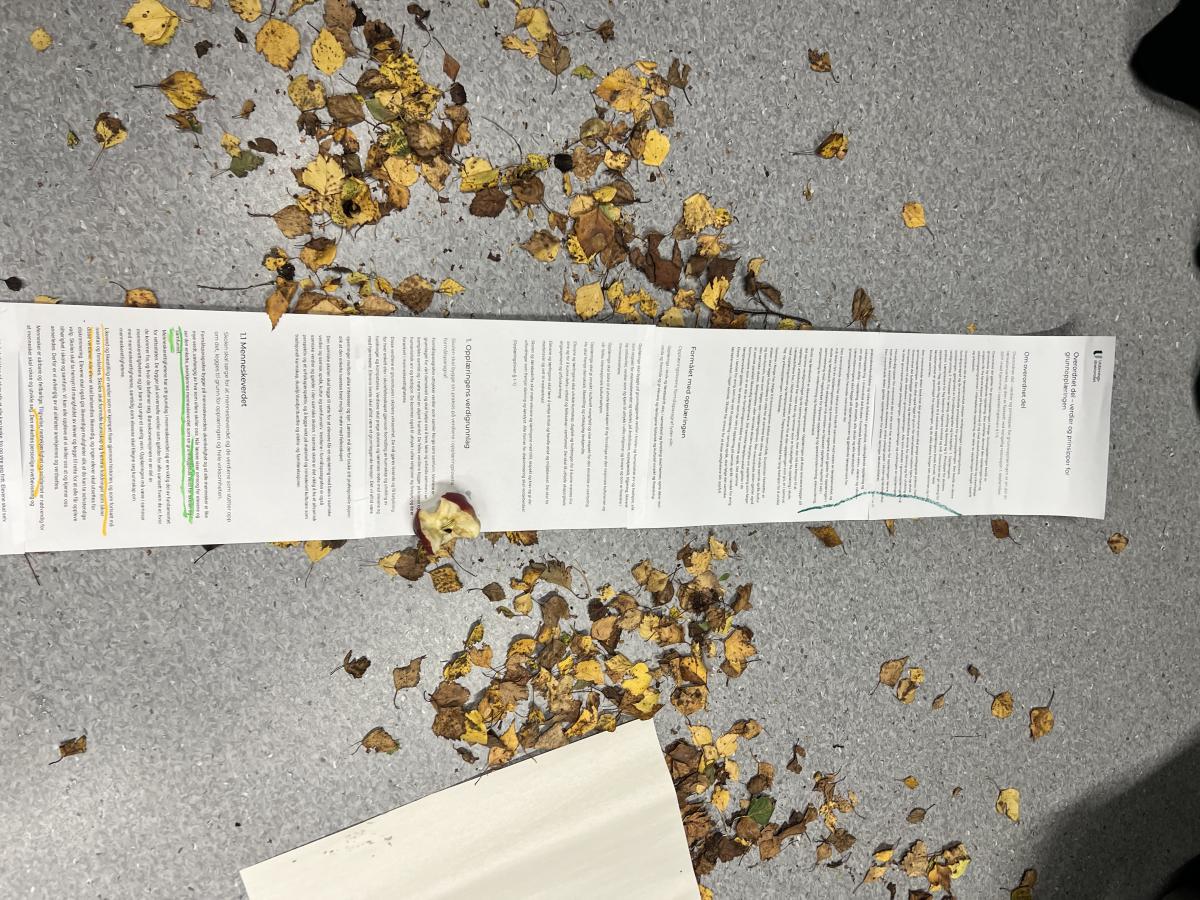

We have some guidelines. More precisely: Guidelines for teaching, guidelines for learning. We are learning new guidelines. Guidelines and instructions that tell us what to teach. Curriculum. They are full of words. Full of ideals. Full of sentences about, what one needs to know to become a citizen in society. What one needs to know to master the subject of drama/music/dance. And about what one needs to be able to do to become a citizen in society. Words. And sentences. Sentences consisting of words that are put together. Combined to make sense. Sense for who?

The following is to be read, as a glimpse into an ongoing research project with colleagues from upper secondary education in Agder and the University of Agder, Faculty of Fine Arts. The project is positioned in the intersection between the following overall themes; art and society, deep learning, lifelong learning and performative pedagogy. And it is framed by the following research question: how can the new curricula for music, dance, and drama in upper secondary school foster new teaching practices?

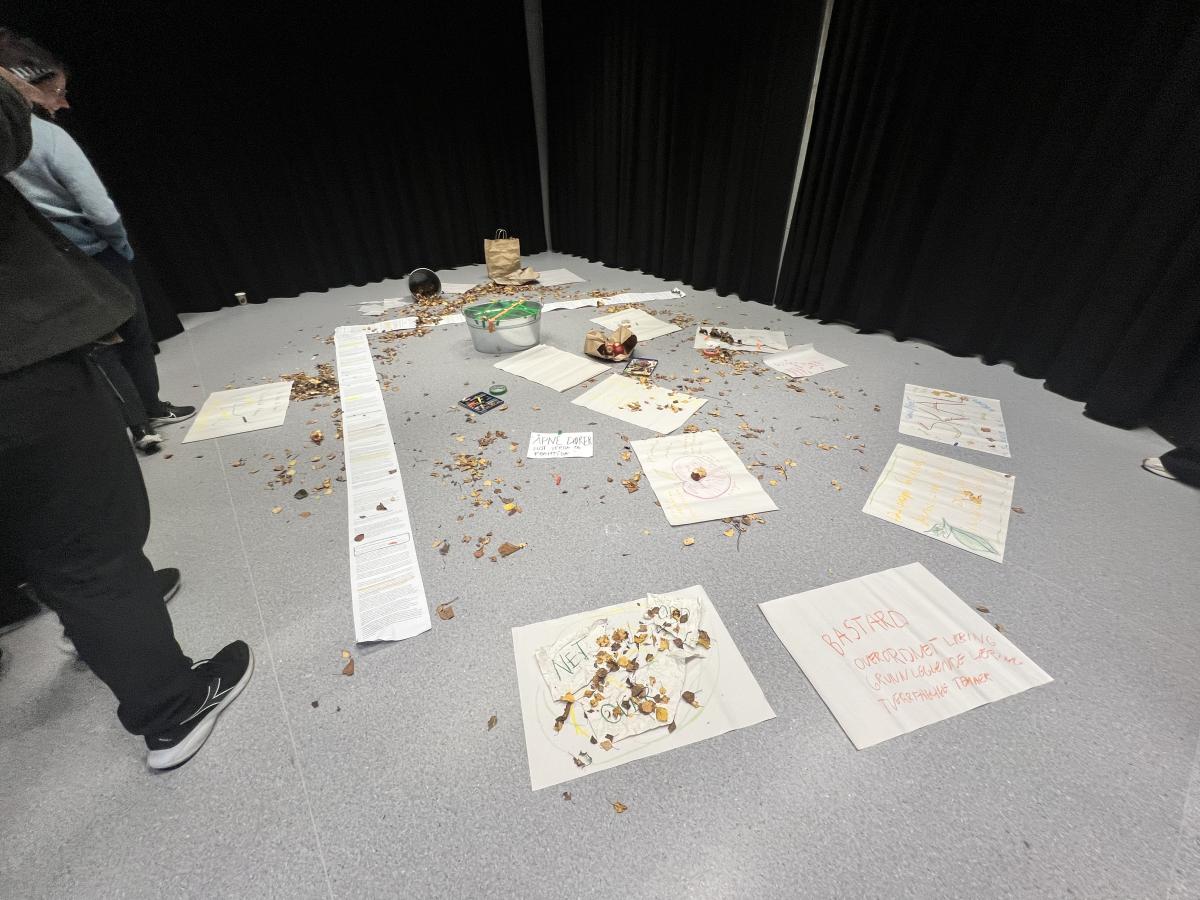

The Music, Dance and Drama programme in Norwegian upper secondary schools (MDD) is unique in both a Nordic and international contexts, as the arts play a central role in providing general university admission qualifications and in fostering students’ overall personal and academic development. Despite their significance, there is a notable lack of research on this educational pathway — a gap the KUSK-project seeks to address1. Part of the project involves developing and carrying out three workshops with students from MDD. The vignette is written short after a meeting between the teachers in the project. In the meeting, we were exploring how the new curricula could become a catalyst for the development of new ways of teaching and learning in arts education. Reading the vignette again, it seems full of itches. Or perhaps more precisely, what Mari Flønes calls ethical itches (Flønes, 2023).

These itches have occurred several times during the KUSK-project and in different contexts. For instance: In dialogue with fellow teacher-participants discussing the purpose of the workshops we are developing and perhaps even the purpose and relevance of the whole research project in itself. Or, when overhearing a couple of participant-students questioning the meaning of the exercises they are invited into and with frustration in their voices proclaiming “This is pointless, I am going to the principal’s office to complain about this project. I want real teaching”. Sometimes these itches create doubts or feelings of insecurity towards the project itself, however my focus in this blog text, is trying to see these itches or the reason for these itches, as part of a process of learning as unlearning (Franklin-Phipps & Zhao, 2022).

Exploring performative pedagogies in upper secondary arts education involves developing new ways of teaching and learning. It is based on a view on pedagogy as a relational, embodied, creative teaching practice, where the student and teacher collectively dive into subjects and creative practices and explore a potential wide range of perspectives (Østern, Illeris et al, 2025; Østern & Knudsen, 2019). Such an understanding of pedagogy also involves a great deal of risk-taking from both the student and the teacher, because its view on learning isn’t about acquiring an already approved set of tools or understandings. Or as Franklin-Phipps and Zhao puts it: “The limited version of learning reflected attachments to an understanding of learning tied exclusively to the institution of schooling, requiring an adult to guide, facilitate, manage, oversee and evaluate that learning” (Franklin-Phipps & Zhao, 2022, p. 78).

With regards to the KUSK-project, the role of the teacher as a guide and facilitator has been discussed and challenged. Especially in relation to the development- and carrying out of the workshops. During the discussions between the teachers there is a curiosity to challenge the thought of a distinct hierarchy between the teacher and the student, however at the same time, a fear of turning the student-participants into experiments in a project and practice that really doesn’t have any relevance or purpose for themselves. Still, a new understanding of both the teacher-role and the meaning of learning seem like an essential aspect, if we want to bring performative pedagogies into arts education in upper secondary education. Opening for exploring new ways of learning isn’t the same as unlearning everything we have learned in becoming teachers. It isn’t about dissolving the role of the teacher in a Rancierian way and the knowledge and power she has (Ranciere, 1991). Instead, it is an invitation to dive into the exploration of themes and subjects with the students, where relations, embodiment and affect works as guiding principles. Not with the intention of transferring a fixed curriculum to the student as a consumer, but as way of creating potential new understandings together. Or questioning established understandings.

Therefore, a central part of the KUSK-project and in my opinion of bringing performative pedagogies into upper secondary arts education, requires that we ask, what arts education can become, rather than stating what it is. From a teacher perspective, such an approach can be challenging to take part of, because it makes you engage in questions related to your own role as a teacher and what traditions and practices that has been part of the process of shaping you as a teacher. Furthermore, it might also lead you to start questioning the teaching practice itself and the structures that frame the practice. Though such a process is challenging and involves a great deal of risk-taking, the concept of learning as unlearning can be a catalyst to start that process. Based on where we are in the KUSK-project, it becomes clearer to me, that part of learning as unlearning involves raising questions about my role as a drama-pedagogue and teaching practice. Thus, learning as unlearning can also be understood as bridging the traditions of the different subjects of art with the contemporary society we live in. Perhaps, even start building bridges to potential futures.

Writer

Kristian Nødtvedt Knudsen

Professor (PhD) i Drama/Teater ved Institutt for visuelle og sceniske fag ved UiA.

References

Franklin-Phipps, A. & Zhao, W. (2022). Learning. In K. Murris (ed.), A glossary for doing postqualitative, new materialist and critical posthumanist research across disciplines (pp. 78-79). Routledge.

Flønes, M. (2023). Diffracting Through an Ethical Itch: Becoming a Response-Able Dance Education Researcher. Journal for Research in Arts and Sports Education, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.23865/jased.v7.5086

Ranciere, J. (1991). The ignorant schoolmaster. Five lessons in intellectual emancipation. Stanford.

Østern, A-L. & Knudsen, K.N. (2019). Performative approaches in arts education. Artful teaching, learning and research. Routledge.

Østern, T.P., Illeris, H., Knudsen, K.N., Jusslin, S., Holdhus, K. (2025). Kunstfagdidaktikk. Universitetsforlaget.

Performing arts in schools

SMIL – Scenkonst med i lärande (Performing Arts in Learning) is a development and research project that aims to explore how performing arts can be integrated as part of the national curriculum and learning environments in Finnish preschools and primary and secondary education. Welcome to follow the project on this blog!

Latest posts

Follow blog