Unveiling the Path to Artistic Mastery: Exploring Doctoral Studies in Fine Arts

Let’s delve into the enriching experiences of Doctoral students at the Academy of Fine Arts, and uncover the profound impact of pursuing a Doctorate in Fine Arts on one’s artistic journey and academic horizons.

Since my beginning years of study, I have identified as an academic. A person who is into research, books, knowledge and writing. During my studies for a Bachelor of Biology, I came to know that I would like to one day do a Master’s degree and a PhD. Now while I am studying for a Master of Fine Art, I still know that I would like to hike the academic path and keep studying. Let’s delve into the enriching experiences of Doctoral students at the Academy of Fine Arts, and uncover the profound impact of pursuing a Doctorate in Fine Arts on one’s artistic journey and academic horizons.

What is the difference between a PhD and a doctorate?

‘Doctorate’ is an umbrella term that includes all kinds of degrees. For example, Doctore of Medicine is a doctorate program. A PhD, which stands for Doctor of Philosophy, is focused on research and generating new knowledge. Whereas, Doctorate degrees are focused on applying knowledge. Both terms are considered equal and the highest level of degree in a field. At the Academy of Fine Arts, a Doctoral program is offered, but other universities offer a PhD program in Fine Arts.

What will you learn/do during the four-year Doctorate program at the Academy of Fine Arts?

To dive deeper into this question and get first-hand answers, I asked Mireia c. Saladrigues what they learned as a Doctoral student. Here is a summary of their response:

– During my time in the doctoral program, I’ve learned two main things. Firstly, I’ve improved my ability to analyse my projects clearly, especially in writing arguments and explanations for my work. This involves critically engaging with existing theories and reflecting on my own research and creative output in extreme detail. While this reflective journey can be challenging, it ultimately leads to fruitful outcomes. Secondly, I’ve developed a deeper capacity for self-expression, which has been personally rewarding. Overall, these two aspects of analysis and clear self-expression have been the most significant learnings for me during this program. –

Another incredible Doctoral student, Orlov Ilya, wrote me this response:

– The main thing I learned from the KuvA Doctoral Programme is the importance of focusing on art theoretical issues of broader relevance, rather than overvaluing one’s own artistic experience. This allows a dissertation work to potentially contribute to the artistic and academic community by generating knowledge that could be beneficial beyond the individual. In turn, engaging with these theoretical issues also informs one’s personal creative process, making it beneficial in any case. I also learned that if a doctoral researcher manages to identify such a theoretical topic, it would undoubtedly receive substantial support from the program in the form of professional advice, supervision, and genuine interest. By ‘theoretical issues of broader relevance’ I of course do not mean ‘how art can save the world’ (it is definitely not going to), but rather specific theoretical plots and conflicts concerning art’s function and principles of artistic thinking. For me, such an issue has become the conflict between the Kantian view of art as a sensuous, aesthetic form and the Conceptualist perspective of ‘art as idea’ and ‘analytic proposition’. –

The program focuses on tip-top artistic work and related research. The study gives the opportunity to conduct independent and creative artistic research. Upon graduation, you will be more ready to develop and renew arts, and make, research and teach.

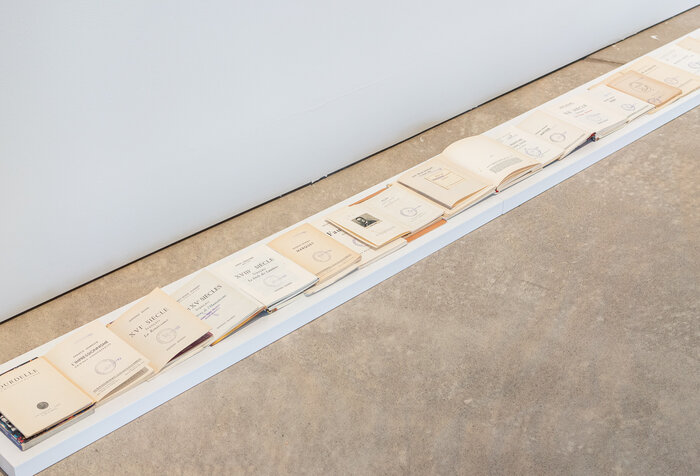

The Doctoral thesis project makes up 170cr of the program and the rest of the credits are from mandatory studies (60 cr) and elective studies (10 cr). This project includes visual art components (up to 140 credits) and a written part (30-170 credits). The visual parts show research findings, while the written part explains the research approach and goals in relation to other research and practices in the field. The whole project includes art exhibitions, curating exhibitions, creating individual artworks, exploring artistic processes, or experimenting with different arrangements and concepts. In short, you will do your artistic process within an institution.

For more insight follow this link to the blog by artistic researchers in the research unit and doctoral programme.

How does one apply for the Academy of Fine Arts Doctorate program?

Application occurs every second year. Autumn 2024 will be the next opening for applications. On this page, there are lots of details about applying. The application includes a comprehensive research plan, portfolio and other supporting documents. Later in the application phase, there will be an interview and time for the applicant to develop their plan.

Is it worth it? /necessary? What does it bring to life?

To answer this important question I asked a Doctoral student. Their reply can be summarised as:

– Choosing to pursue a doctorate felt like a natural progression due to the inquiry-based nature of my art projects since 2008. The practice-based approach in Finland provided me with the time and resources to delve deeply into projects, such as studying an iconic act of iconoclasm. This journey allowed me to have the position to access invaluable archives, interviews, and collaborations with scientists, enriching my research and bringing a sense of privilege and joy. Overall, the program has significantly shaped my artistic journey and broadened my horizons. –

Do you have any tips for someone wanting to do the doctoral programme?

To gather some top tips I got first-hand answers from Mireia that can be synthesized as:

- Be certain that you truly want to pursue a doctoral program as it involves not only conducting your own research but also contributing to the field through symposiums, conferences, and staying updated with colleagues’ developments.

- Choose a program that aligns with your practice, whether it’s more practice-based or theoretical, and consider the structure of the final thesis requirements.

- Select your supervisor carefully, aiming for someone who aligns with your interests and can offer valuable guidance and insights.

- Embrace your specialisation within a specific area and reclaim the uniqueness of your work, viewing the doctoral program as an opportunity to explore and test ideas rather than solely building theories.

- Remember to maintain a balance between seriousness and practicality, allowing yourself room for experimentation, playfulness, and enjoyment in the research process.

Ilya wrote me this response that strongly inspired me to read and write.

– As for the tips for those who are considering applying for the doctoral programme, I do not really feel accomplished enough to give advice; I have not even managed to complete my studies yet. I would just mention a few very basic things. The essential skill for a doctoral student is the ability to produce coherent theoretical texts adhering to basic academic standards. The official principle of the doctoral programme emphasises the quality of artistic works as the main evaluation criterion. This should not be misunderstood in the sense that artistic proficiency alone is sufficient. Regardless of the professional level of artworks or the extent of artistic career achievements, the production of quality theoretical text remains an integral part of doctoral study and its successful completion. In other words, aiming for a Doctor of Arts degree involves the decision to become an artist-writer.

Becoming a ‘writerly artist’, however, is a worthwhile endeavour in itself, even if you are not going to enrol in doctoral studies and become an artist-researcher. From my experience, engaging with art theoretical texts significantly enhances artistic thinking and facilitates the generation of clearer artistic ideas.

It is true that for many artists, writing is a challenging task. Not everyone feels as comfortable in the realm of words and theoretical concepts as amidst visual images and artistic ideas. This hardly comes as a surprise: if writing were for artists as instinctive as engaging with visual and plastic materials, many of us might have chosen the path of a writer rather than that of an artist. Yet, it is worth considering the flip side: many of the most influential artists of the last century have also been writers and theorists, leaving behind a substantial written legacy.

Theoretical writings by artists have long formed a tradition, amounting to a distinct corpus of literature. These texts vary widely in style and substance, yet they share a unique ‘voice’ – one markedly different from that of an art critic, art historian, or curator. It is characterised by its ‘insider’s perspective’ on the creative process and often represents an attempt to comprehend the principles of artistic thinking.

Writerliness emerged as a strategic approach for artists in the avant-garde era of the 1910-1920s.1 During this period, starting with cubism and early abstraction, art evolved into a philosophical theoretical practice. This implied the artists’ capacity to articulate theoretical positions and present them publicly. Key texts from this era, written by artists, are compiled in the anthology ‘Art in Theory, 1900-1990,’ edited by Charles Harrison and Paul Wood.2 This book is accessible online, and a copy is also available in the Uniarts Helsinki library.

It is especially worth looking at the texts of conceptual artists from the late 1960s and early 1970s. Conceptual art is where the figure of an artist-theorist, a professional artist-intellectual, was shaped, speaking on equal terms with professional art theorists and art critics. In this sense, the texts by the conceptualists might just be the most significant contribution artists have ever made to the philosophical theory of art. Many of these texts can be found in the publication ‘Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology,’ edited by Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson.3 This book is also available online.

It is also worth noting that the core theoretical bibliography of the Kuva Doctoral Programme is centred around Artistic Research theories. This literature forms a significant part of the study material in many courses within the programme. So it would make sense to familiarise oneself with this theoretical direction in advance. I refrain from listing specific authors, as the field is developing dynamically; but an online search for ‘artistic research bibliography’ could lead to the most recent publications.

Regarding reading practices. Professional reading naturally involves writing. It is a good idea to draft a paragraph about every theoretical text read, capturing the main points and adding some reflections on it. Noting down quotations can be helpful, but writing ‘in your own words’ is crucial for learning to create original text. This practice is not merely an exercise. By making such notes, one creates a resource that can be potentially integrated into their own academic work. Of course, remembering to include a reference to the authors read is essential.

The thoughts I have shared above are drawn from my own theoretical perspectives, which may not fully align with the views of other colleagues or the programme’s official stance. The Kuva Doctoral Programme values a broad spectrum of ideas and encourages a dialogue among them. If you are looking for more specifics or advice, it is a good idea to get in touch with the programme directly. –

- For history of artists’ writerliness and its impact on art see: Roberts, John. “Writerly Artists: Conceptual Art, Bildung, and the Intellectual Division of Labour.” Rab-Rab: journal for political and formal inquiries in art 1. 2014.

- Wood, Paul, and Charles Harrison, eds. Art in Theory: 1900-1990. Blackwell, 1999.

- Alberro, Alexander, and Blake Stimson, eds. Conceptual art: a critical anthology. MIT press, 2000.

Does it cost? Is there funding available?

At the moment there isn’t a tuition fee. Also, The Academy of Fine Arts doesn’t provide funding for doctoral students. However, there are possibilities to apply for funding from other parties. For example, non-EU students can apply for the Finland Fellowships fund. Some people save up before studying and others work part-time.

Where else is a Doctorate of Fine Arts offered?

All over the world! Poland, Portugal, Japan, England, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Italy, Malaysia, Florida…

Bibliography

https://www.waldenu.edu/online-doctoral-programs/resource/what-is-the-difference-between-a-phd-and-a-professional-doctoral-degree

https://www.phdportal.com/search/phd/visual-arts/europe

https://www.uniarts.fi/en/study-programmes/doctoral-programme-in-fine-arts/

Life of an art student

In this blog, Uniarts Helsinki students share their experiences as art students from different academies and perspectives, in their own words. If you want to learn even more regarding studying and student life in Uniarts and Helsinki, you can ask directly from our student ambassadors.

Latest posts

-

Helsinki Survival: Affordable sports options in Helsinki for students

-

Helsinki Cycling II: Short Distance Trips for a Relaxing Weekend with Your Bike

Follow blog