Why teach drama and theater?

Drama and theatre teachers at the University of Iceland, Rannveig Björk Thorkelsdóttir and Jóna Guðrún Jónsdóttir, explore how drama and theatre open doors to transformative learning experiences by fostering empathy, self-expression, and critical thinking, equipping students to navigate an ever-changing world with confidence and imagination.

In this blog, we ask why teach drama and theatre? What can drama and theater education do that other subjects can‘t do?

Isn’t drama and theater education just another subject in an over-filled curriculum in primary education?

The answer is no, and we like to tell you why.

Drama in schools

We believe there is something special about the art form of drama and how it can work as a practice aimed at learning in general and as a subject on its own. We also believe students develop their emotions through drama, empathy, and self-control. They build their self-confidence and creativity, boost their powers of expression, and improve their social and cooperative skills. We also believe that the uniqueness of drama comprises, inter alia, its ability to harness, in equal measure, intellect, creation, and physical endowments. Drama is an agent of change, nourishing the student’s social and emotional development (Rannveig Björk Thorkelsdóttir, 2016).

Theatre in schools

There is also something special about going to the theatre and the magic it makes. Bringing a child to a theatre is potentially a life-changing experience and an opportunity for a unique kind of learning. The theatre is a world of “what ifs.” The child is transported to a make-believe world where anything can happen. The theatre can also be a place of learning. Learning can occur through theatrical literacy, storytelling, and sitting and watching a performance without distraction. The benefit of children attending the theatre is that it encourages empathy and cultural awareness; it develops critical thinking skills, promotes well-being, and is fun (Thorkelsdóttir and Jónsdóttir, 2023).

Icelandic context

To give it some context, drama, since 2013, has been part of the Icelandic primary school curriculum both as a method and subject.

- Drama, as a method, enriches and enhances learning in subjects such as mother tongue, sociology, history, and foreign languages and plays a leading role in integrating subjects and subject areas. The lesson must include “teacher in role, living through drama, self-expression, growing through drama, work in pairs, and learning through drama” (Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, 2013).

- Drama is a subject in the curriculum in Iceland, education in drama includes training students in the methods of the art form and dramatic literacy in the widest sense, enriching the student’s understanding of themselves, human nature, and society. When students take part in drama, it gives them the opportunity to put themselves in the shoes of others in an imagined context, which can encourage the students to talk and communicate from a different point of view in the safety of the classroom. The lessons need to include “improvisation, the student’s ability to take on a role, work with text, work in a group, work with many forms of theatre, take on a differed acting style and be able to see the connection between the performer and the audience” (Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, 2013)

Rannveig Björk Thorkelsdóttir (2012) suggests that whether the teacher is working as a teacher in a role for the benefit of the process or leading the students working on a text on acting style or improvisations for the benefit of a product, both teacher and students are working together on how to express and enrich their feelings. They seek to understand and recognize the relationship between culture and values. According to O’Toole and O’Mara (2007), there are four ‘paradigms of purpose’ in using and teaching drama. They are cognitive/procedural, which means gaining knowledge and skill in drama; expressive/developmental, which means growing through drama; social/pedagogical, which means learning through drama; and functional/learning, which means learning what people do in drama. In many texts about drama in education, these purposes are interwoven. They also talk about three sets of dimensions in drama: making (playwright, improviser, director, designer), presenting (actor, technical crew), and responding (audience, dramaturge, critic) (213-214).

O’Toole and Dunn (2021) also argue that drama should be taught in every classroom in the following way: Drama is about exploring, discovering, creating- and performing. Principally, especially in the primary years, it is about creating models of behavior and action that can be practiced and performed safely /…/ in any human context. Through drama, the students can learn to interact with one another in a safe space and try out different societal roles.

So, what is a safe space?

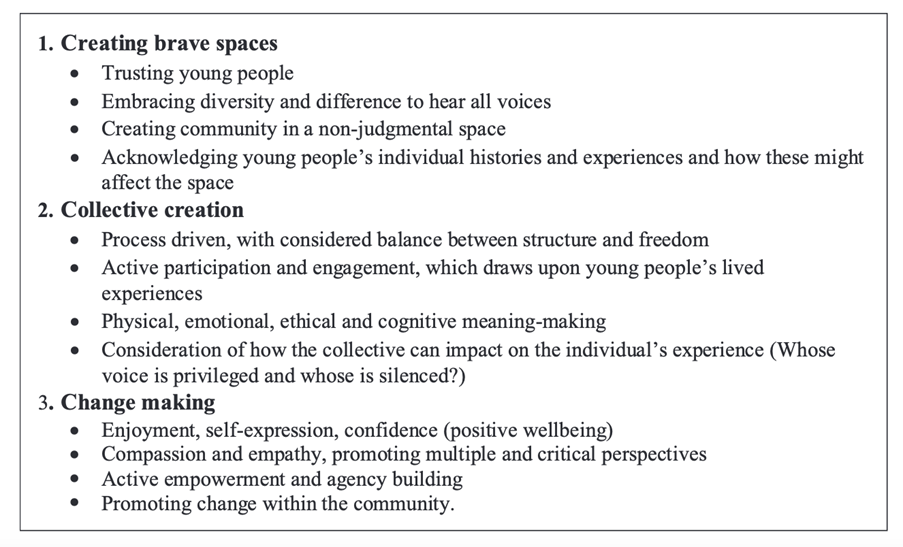

In a project called ArtEd, safe space and collaborative environment are described as follows:

According to Dunn and O’Toole, there are some characteristics that drama teachers have to bear in mind when teaching drama. These characteristics included:

- Space and collaboration: drama keeps children active physically as well as mentally.

- Motivation: drama is exciting, and the children enjoy doing it; drama is fun (Thorkelsdóttir, 2018).

- Emotion: drama generates and, indeed, at times, provokes emotions in the learning environment, such as excitement, humor, and sadness.

- Focus: drama adds value and purpose to classroom tasks by framing them in realistic purpose based on life contexts (Dunn and O‘Tool, 2021).

To prepare drama teacher

In considering ways to prepare initial teacher educators in drama, research from Thorkelsdóttir (2016) found that drama teachers consider heavy workload and lack of time as the most difficult part of teaching. They must also teach drama as a class activity, teaching up to 50 students simultaneously. Teachers also talk about the need for communication with other teachers, and this lack of community creates feelings of isolation. But what matters the most is not having a proper space for drama, like a drama studio, or at least a room suitable for teaching drama (Thorkelsdóttir, 2018).

Drama as part of the arts

Drama as a part of the arts makes a strong claim as part of the education system. Students can construct new aesthetic knowledge through the arts and deepen their human impulses and experiences. Drama is, by nature, an integrative practice where all art forms are combined.

Michael Anderson (2012) points out that drama is unique in the education system, at the intersection between intellectual, creative, and embodied education. Furthermore, Anderson holds that drama teaching is transformative, meaning that drama can support the academic, social, and emotional growth of young people. Drama education, and arts education in general, is a pedagogy with a heritage that has the potential to modernize schooling (p. 10).

On the other hand, Gert Biesta (2018) asks what the arts can contribute. Is it to let young people relate to what it means to express themselves, their desires, and their dreams? He believes that art is not just an exploration of what it means to be in dialogue with ‘the world’ or dialogue with ‘the other.’ Biesta describes the power of art in educational work as follows:

“Art makes our desires visible and gives them form, and by trying to come into dialogue with what or who offers resistance, we are at the very same time engaged in the exploration of the desirability of our desires and their rearrangement and transformation.” (Biesta, 2018, p. 18)

We believe that drama, theatre, and arts education are important in this chaotic world, and perhaps more so today than ever, because of young people’s challenges in modern society. Through drama, the students can learn to interact with one another in a safe space and try out different social roles, and through role-playing, they can explore aspects of what it means to be human (Thorkelsdóttir, 2018). By having drama, theatre, and arts education in schools, we give all students the opportunity to participate in a “What if ” world regardless of their social class. In a constantly changing world where technology is developing rapidly, drama has something to offer other subjects do not have because it gives us the opportunity to imagine and enact futures and try out ideas in a “What if” world (Thorkelsdóttir and Jónsdóttir, 2022).

Writers

Rannveig Björk Thorkelsdóttir and Jóna Guðrún Jónsdóttir

Drama and theatre teachers at the School of Education, University of Iceland

References

Anderson, M. (2012). Master class in drama education. Transforming teaching and learning. London: Continuum.

Biesta, G. (2018). What if? Art education beyond expression and creativity. In C. Naughton, G. Biesta, & D. Cole (Eds.), Art, artists and pedagogy: Philosophy and the arts in education (pp. 11–20). London and New York: Routledge.

Ministry of Education, Science and Culture. (2013). The Icelandic national curriculum guide for compulsory schools – with subject areas. Reykjavík: Ministry of Education, Science and Culture. https://www.menntamalaraduneyti.is/utgefid-efni/namskrar/adalnamskra-grunnskola/

O’Toole, J. & O’Mara, J. (2007). Proteus, the giant at the door: Drama and theatre in the curriculum. In L. Bresler (Ed.), International handbook of research in arts education (pp. 203-218). Dordrecht: Springer.

O’Toole, J. & Dunn, J. (2015/2021). Pretending to learn. Teaching drama in the primary and middle years. Australia: DramaWeb publishing.

Thorkelsdóttir, R. B. (2012). Leikið með listina [Play with Drama]. Reykjavík: www.leikumaflist.is.

Thorkelsdóttir, R.B. (2016). Understanding drama teaching in compulsory education in Iceland. Doktorsritgerð [Doctoral Thesis]. Trondheim: Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Thorkelsdóttir, R. B. 2018. What are the enabling and what are the constraining aspects of the subject of drama in Icelandic compulsory education? In T. Chemi & X. Du (Eds.), Arts-based methods in education around the world (pp. 231–246). Denmark: River Publishers.

Thorkelsdóttir, R.B., and Jónsdóttir, J.G.þ (Eds.) 2022). Performance and Performativity. Aalborg Universitiesforlag. Research in Higher Education Practices.

Performing arts in schools

SMIL – Scenkonst med i lärande (Performing Arts in Learning) is a development and research project that aims to explore how performing arts can be integrated as part of the national curriculum and learning environments in Finnish preschools and primary and secondary education. Welcome to follow the project on this blog!

Latest posts

Follow blog