Interview with Sasha Huber: on ‘pain-things’, reparative interventions and exposing the roots of ‘scientific’ racism

Sasha Huber (CH/FI) is a Helsinki-based visual artist of Swiss-Haitian heritage. In her work, she addresses topics such as politics of memory and belonging, and colonial and racist histories. She is currently also working on her practice-based PhD. Arts Management student Jenni Pekkarinen interviewed Sasha Huber about her artistic work, the impact of this turbulent year, and questions of identity and anti-racism.

In your statement on your website, you say that the primary incentive for your artistic work has been the exploration of your Swiss-Haitian roots and identity via colonial history. When did this exploration become the driving force for your work and in what ways has it affected your artistic work?

My roots have been the starting point for my artistic journey, if we could call it that. It started in 2004, to be exact, which is when I made my first portrait series Shooting Back – Reflection on Haitian Roots. That was the first time I worked with the compressed-air staple gun to create portraits of Christopher Columbus and the dictators of Haiti. They were all individuals who had contributed to the troubles in Haiti. Even though Haiti was the first Black Republic in history. In 1804, the enslaved population, which outnumbered the French colonizers, staged a revolution and freed themselves from their shackles. This, however, did not come without a very high price, which also contributed to Haiti’s complicated and challenging future. That first project was strongly informed by decolonial thinking and action, even though I did not yet have the vocabulary for my practice then.

In what ways do you think your work has changed over the years and can you identify some milestones in your career?

The staple gun has a powerful symbolism and it allowed me then, and still today, to convey issues that I feel most concerned about. What evolved from then on is that the shooting with metal staples was, at first, a way to literally ‘shoot back’ and defend the dead. What changed over time was that my methodology evolved from ‘shooting back’ to ‘stitching up colonial wounds’. I started putting my energy into portraying individuals who have been harmed by colonialism then and now, and who have been silenced in history. It has become a form of caring and making visible the wounds that have been inflicted. I came to call this way of working ‘pain-things’.

One major impact on my practice was also when I started making reparative interventions that could be understood as a form of performance. Even though I never saw myself as a performance artist in the classic sense, nor a portraitist, but rather as a conceptual, visual artist-researcher who works in a variety of media. The interventions have enabled me to place my body into spaces around the world while negotiating with local collaborators, and to intervene in colonized landscapes as a whole.

How do you think your artistic work has affected your own identity?

I feel in my case this was more another way round. Since the beginning, doing art has been informed by one part of my identity, which happened due to an urgent need I had at that time. It was about my inability to visit my family in Haiti due to political problems that made traveling there unsafe. This made me look more closely into the reasons why this was the case, and that research inspired me to express my opinions by making my first art project using the compressed-air staple, as I mentioned earlier. In time, my work broadened out and taken together helped me make more sense of the world we live in. In terms of my background, my identity was that of a graphic designer, which I studied in Zurich (BA) and Helsinki (MA). But I felt strongest when expressing myself artistically, rather than with the tools that graphic design gave me. Although, in time, I also started using those skills in my practice.

You are currently working on your practice-based PhD at the Zurich University of the Arts in cooperation with the Art University in Linz. Could you tell us a little bit about that?

Originally, I started practice-based doctoral studies at Aalto University and decided later to go into the Swiss PhD system, as the theme of my Swiss-based research on colonialism was both timely and had to be presented on-site. Criticizing your own culture is rarely possible in your own country. I am grateful to have been able to cross the boundaries between the two countries so as to shed light on colonial and racist histories, echoes of which appear everywhere, even in outer space.

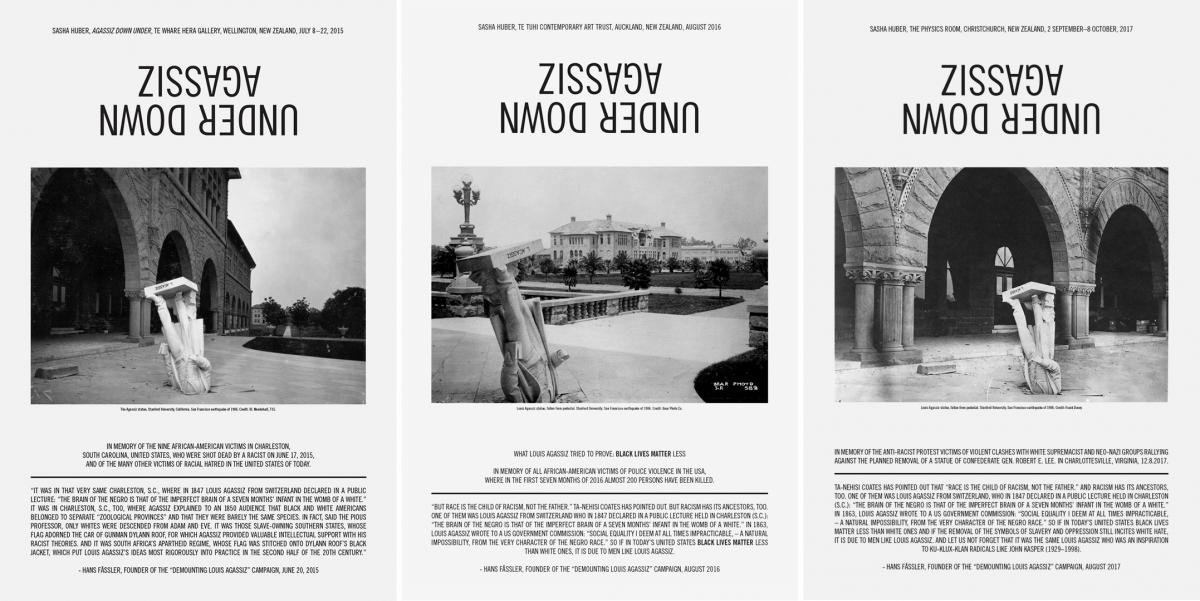

My practice-based PhD project deals with my artistic research work, which evolved out of my becoming a committee member of the transatlantic, cultural-activist campaign Demounting Louis Agassiz. The campaign was founded by the Swiss historian Hans Fässler in 2007. The aim was to advocate the renaming of the Agassizhorn mountain in the Swiss Alps. The mountain was named by the glaciologist and racist Louis Agassiz (1807-1873) himself, and we applied to rename it Rentyhorn. Renty was an enslaved Congolese-born man who Agassiz ordered to be photographed on a South Carolina plantation in 1850 to ‘prove’ the inferiority of black people. I carried out my first intervention on the mountain and made the renaming a reality. This was the start of my working with interventions, first in Switzerland and then in Brazil, Scotland, New Zealand, the USA, and Canada. My research exposes specific roots of ‘scientific’ racism (defined by Louis Agassiz), and asks how art can contribute to healing the wounds inflicted by colonialism then and now, with an emphasis on indigenous peoples and peoples from the African diaspora, via anti-racist creativity.

This has been quite a turbulent year in many ways. As an artist, how do you deal with and react to social and political movements and conflicts?

Indeed, this year – and possibly also next year – is unprecedented and challenging. We cannot prepare for this kind of situation. We have all had to become creative, adapt, and find new ways of creating and disseminating work temporarily. But since most of us are in the same situation there is a sense of solidarity and understanding. But it is quite a complicated situation altogether.

As I mentioned earlier, my whole starting point for doing art was about reacting to situations in our world that happened in the past and the present. Movements are part of this as well. For example, unjust and racially motivated killings have been happening historically for a long time, but after George Floyd’s killing on May 25th, the Black Lives Matter solidarity protest movement started to grow around the world. This made an awakening possible. A huge section of the white population started to open their eyes and understand what a precarious situation many BIPOC people are in, and not only in the US. At the first BLM protest in Helsinki in 2016, there were a couple of dozen people and, this year, there were many thousands of us. It was powerful to see. What was to be expected though was that, for many people, this passion dropped off a lot soon after. The naturally occurring pandemic takes attention away from eternally returning issues of inequality. New normals come and go, but luckily art history remains to do its share and record the moral arc of the universe.

And finally, a question about the role of art universities: how do you see the role of art universities and their possibilities to be actively anti-racist and support diversity and pluralism in society?

It is important that the universities, in general, have started working on or intending to take steps to look critically at their whole structure from inside and out. What is to be hoped for is that, not only students, but also higher education professionals, will be more diverse. It would also be good to integrate the relevant courses to be part of the mandatory curriculum, and that they were not limited to being occasional special courses that can easily be dropped again when the issues related to equality do not seem so urgent any more. Art history also had generally been written by the dominant culture, and non-western art history has not got the attention it deserves. Maybe future art historians will learn to do things differently. In the end, if caring anti-racist changes were to happen collectively, it would help to establish a more equal society.

Read more about Sasha Huber and her artistic work on her website.

If you happen to be in Prague or Paris, remember to visit her ongoing and upcoming exhibitions:

Until 10.12.2020 (extended after 2nd lockdown)

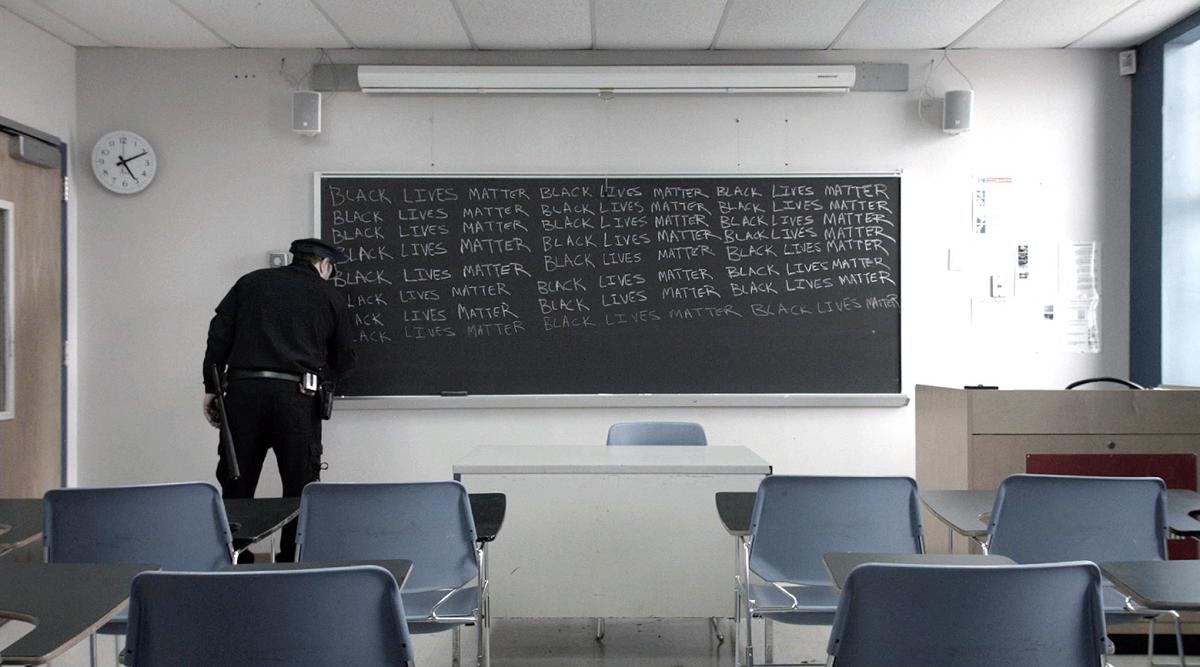

Black Lives Matter

Sasha Huber & Petri Saarikko

Artivist Lab Gallery, Prague

Artivistlab.info

5.1.-20.3.2021

Untie Knots, Weave Connections

Sasha Huber & M’Barek Bouhchichi

Finnish Institute in France, Paris

The AM Times

Have you ever wondered what arts management is and what’s its role in promoting sustainability, diversity and equality? Join us for a peak behind the curtains and learn from arts managers themselves!

This blog is a space for current arts management topics featuring students’ opinion pieces and reflections, interviews with field professionals from around the world, and occasional guest posts.

Latest posts

Follow blog